Now, there are various answers that could be given to such claims (see here, here, here and here for a few) but my favorite is to look at the 'deregulation era' from the eyes of poor people around the world. If your concern is the worlds truly poor - those living in absolute poverty - the 'deregulation era' is an absolute god sent.

Take Hans Rosling, who gave a Ted Talk on this very thing - showing how our preconceived notions of poor countries are extremely outdated, see here. He shows that many countries, especially in Asia, but also Latin America and Africa, that have been poor for so long are now quickly moving up the economic ladder. But this was in 2007, the leftist replies, surely it's outdated, no?

But then a couple of prominent economists noticed the same thing. MIT's Maxim Pinkovskiy and Columbia's Xavier Sala-i-Martin published a paper showing:

The conventional wisdom that Africa is not reducing poverty is wrong. Using the methodology of Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin (2009), we estimate income distributions, poverty rates, and inequality and welfare indices for African countries for the period 1970-2006. We show that: (1) African poverty is falling and is falling rapidly; (2) if present trends continue, the poverty Millennium Development Goal of halving the proportion of people with incomes less than one dollar a day will be achieved on time; (3) the growth spurt that began in 1995 decreased African income inequality instead of increasing it; (4) African poverty reduction is remarkably general: it cannot be explained by a large country, or even by a single set of countries possessing some beneficial geographical or historical characteristic. All classes of countries, including those with disadvantageous geography and history, experience reductions in poverty. In particular, poverty fell for both landlocked as well as coastal countries; for mineral-rich as well as mineral-poor countries; for countries with favorable or with unfavorable agriculture; for countries regardless of colonial origin; and for countries with below- or above-median slave exports per capita during the African slave trade.The authors explain their findings here. The New Republic as well as Blue Matter blog comment here and here.

Matthew Yglesias quotes another study from the World Bank:

Just over 25% of the world’s population (1.4B people), lived in extreme poverty in 2005, according to a report released this month from the World Bank (”Global Economic Prospects 2009: Long-term prospects and poverty forecasts“). This has fallen from 42% in 1990, when the bank first published its global poverty estimates. All regions of the world have seen gains. Rapid economic growth east Asia in particular has led to a dramatic decline in global poverty. In China the share of the population getting by on $1.25 a day, or less, fell from 60% to 16%.The Economist magazine has more here.

Matthew Yglesias later comments:

Amidst all these problems in the United States, it’s worth recalling that for much of the world these are actually the best of times...

American politics is, naturally, going to remain focused primarily on the problems of Americans. But ultimately the problems of poor people in the developing world are much more severe than any of our problems, and growth in poor countries is extremely good news.Even the Huffington Post picked up on the drastic change:

In the 1990s, "people could only feed themselves, and some even starved. Children could not afford to go to school, and many could not even finish primary school," said Liu Jiandang, a 41-year-old former farmer. "Now, we've got paved roads, new houses, phones and vehicles. I run a hotel that can host 20 to 30 tourists and some rooms have TV sets, air conditioners, hot water and bathrooms."

With her profits topping 50,000 yuan ($7,000) a year, Liu can afford to send her 19-year-old son to vocational college and her 10-year-old daughter to primary school. "Our lives are so much better than before," she said.Okay - you say, but surely the financial crisis has reversed most of these trends, right? The answer is no. According to Dani Rodrik, professor at Harvard Universities International Development program, writes:

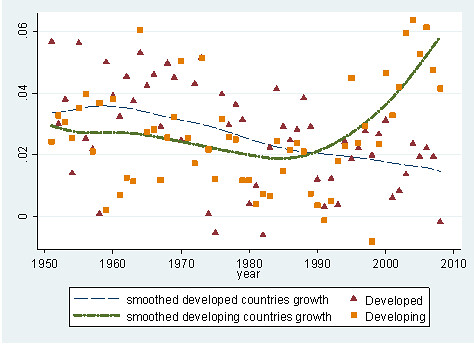

For the first time ever, developing countries as a group grew have been growing faster than industrial countries. Not only that, as the figure makes clear, the growth differential between the two groups has been widening in favor of the poor countries.

And it isn't just China, India, and a few countries that have been doing well. For a change, Africa and Latin America actually experienced some convergence with rich countries over the last decade.

Many analysts have projected these trends forward and predict rapid global growth, largely off the back of emerging and developing nations. In the words of a Citigroup report, "this time will be different."He provides this eye opening graph:

Notice the dramatic turnaround, starting around the 1980's and moving upwards quickly thereafter. This is all GREAT news from a developing countries perspective and it seems like the great recession hasn't slowed it down!

What would the future look like if this trend is to continue? Tim Taylor gives the numbers:

To get a sense of the change, compare the rank order of the economies of the world in 2009 and 2050. In 2009, the U.S. is the world's largest economy. By 2050, U.S. economy will be about 2.5 times as large--and is projected to be in third place in absolute size, behind China and India. What other countries move up the rankings notably by 2050? Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, Nigeria, and Vietnam. To my 20th century mindset, some of those countries just don't seem like global economic heavyweights. Time to start adjusting my mind to the coming realities.More can be found on his blog post here.

The private sector is catching on too, as Alan Taylor, a Senior Adviser at Morgan Stanley wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine:

A broad range of economic figures suggest that emerging markets are catching up to developed markets. As the Great Recession fades, this trend is likely to continue. The emerging-market history of low growth and high volatility is fading, while developed markets are experiencing more instability and financial impairments. Emerging markets have decreased their debt-to-GDP ratios, even as developed markets, including the United States and some in Europe, are letting theirs rise. In a sign of convergence between emerging and developed markets, health and schooling levels in emerging-market countries are now comparable to those seen in developed markets around 1975, with the gap continuing to narrow. And average levels of political and economic freedom in emerging markets have also improved dramatically in the last two decades. Although emerging markets have not yet achieved parity with developed markets…they now appear more stable and better positioned to enjoy sustained growth than they did a generation ago.Even Jay Ulfelder is convinced, he writes:

To my mind, the trends Alan Taylor identifies are the start of the big development story of the 21st century. After a century in which the global political economy was primarily characterized by the yawning gap in wealth and power between the so-called First and Third Worlds, that gap is finally narrowing. Economic growth is accelerating in countries long mired in a “poverty trap,” and the economic and political benefits of that trend are extending to more and more of the world’s human population. Hundreds of millions of people still live in abject poverty, under authoritarian rule, or both, but the share of the global population living in deep poverty is notably lower than it was just a couple of decades ago, and the economic takeoffs occurring in many long-poor countries suggest that trend is only broadening.I leave you with a quote from a study on this very thing from the Brookings Institute (pdf) :

The greatest surprise, however, is the one taking place in Sub-Saharan Africa. Between 1980 and 2005, the region’s poverty rate had consistently hovered above 50 percent. Given the continent’s high population growth, its number of poor rose steadily. The current period is different. For the first time, Sub-Saharan Africa’s poverty rate has fallen below 50 percent. The total number of poor people in the region is falling too.If you consider all humans of equal value, regardless of race or nationality, the 'deregulation era' has to be considered a great era and a positive change over previous periods of human history - and this is true, even assuming the worst case assumptions of the liberals and lefties of the world.

Update: More here, here and here(pdf). (Originally published 7/29/2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment