Imagine that you lived in Beverly Hills, among the richest people in the United States. Some of your friends were the kids of executives at Fortune 500 companies. Others were the kids of famous Doctors, Lawyers, and some were the kids of hedge fund managers. While all relatively rich, assume there was quite a range of wealth from really rich, to filthy rich.

Further assume, that one day, a bleeding heart liberal starts feeling bad for the really rich. Her complaints are along the lines of: "The really rich can't eat out at the $500/plate restaurants, they have to settle for the $100/plate restaurants, or, god forbid, make sandwiches at home". Her complaints continue: "The really rich can't afford the Lamborghini's or Ferrari's, they have to get by with the - GASP! - BMW's and Mercedes Benz's". Worst yet, "the really rich actually have to live in mansions with no ocean view, or golf courses". Most heartbreaking of all, "the really rich have to actually prioritize their lifestyle and set a budget. They can't go to Europe on a moments notice, they can't eat out everyday".

Now further assume that said bleeding heart liberal decided to set up an "alleviate suffering" fund that took away from the filthy rich to give to the really rich. Such a fund would help equalize Beverly Hills and "bring people together". But instead of making this fund voluntary, the bleeding heart liberal wanted to enforce this through the city. She wanted to make it a city tax that merely takes from the filthy rich and gives to the really rich. Her arguments, again, are to "alleviate suffering".

What would your reaction be if you were suddenly transplanted to that society and debate? Would you support the "Beverly Hills tax"? I am not one of those that believes there are absolutely no circumstances that justify forcibly taking the wages of one to give to another. But such circumstances have to be met with atleast reasonable justification. Yet simply moving money around amongst the worlds richest people does not seem to me like an acceptable justification.

Such is the image that comes to mind whenever I have a discussion with a liberal about increasing redistribution via taxes to help the USA "poor". It's the image my dad and uncles, who immigrated to the United States in their twenties from ranch life in the poorest parts of Mexico, gave me. It is certainly how they viewed me and my cousins growing up - no matter what our circumstances, be it growing up in Compton (as I did), living off of the income of mechanics, gardeners, or window tinters - we were all blessed beyond their wildest dreams. Where they had to eat tortillas off the dirt floor, work in fields in the scorching heat where there were no "sick days" or "vacation time", even the McDonalds cashier can seem privileged. And this view isn't far from reality. Even the "poor" in the United States are among the richest in the world (see here and here).

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Ending slavery

Thomas Sowell|Posted: Feb 08, 2005 12:00 AM

To me the most staggering thing about the long history of slavery -- which encompassed the entire world and every race in it -- is that nowhere before the 18th century was there any serious question raised about whether slavery was right or wrong. In the late 18th century, that question arose in Western civilization, but nowhere else.

It seems so obvious today that, as Lincoln said, if slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong. But no country anywhere believed that three centuries ago.

A very readable and remarkable new book that has just been published -- "Bury the Chains" by Adam Hochschild -- traces the history of the world's first anti-slavery movement, which began with a meeting of 12 "deeply religious" men in London in 1787.

The book re-creates the very different world of that time, in which slavery was so much taken for granted that most people simply did not think about it, one way or the other. Nor did the leading intellectuals, political leaders, or religious leaders in Britain or anywhere else in the world.

The dozen men who formed the world's first anti-slavery movement saw their task as getting their fellow Englishmen to think about slavery -- about the brutal facts and about the moral implications of those facts.

Their conviction that this would be enough to turn the British public, and ultimately the British Empire, against slavery might seem naive, except that this is precisely what happened. It did not happen quickly and it did not happen without encountering bitter opposition, for the British were at the time the world's biggest slave traders and this created wealthy and politically powerful special interests defending slavery.

The anti-slavery movement nevertheless persisted through decades of struggles and defeats in Parliament until eventually they secured a ban on the international slave trade, and ultimately a ban on slavery itself throughout the British Empire.

Even more remarkable, Britain took it upon itself, as the leading naval power of the world, to police the ban on slave trading against other nations. Intercepting and boarding other countries' ships on the high seas to look for slaves, the British became and remained for more than a century the world's policeman when it came to stopping the slave trade.

"Bury the Chains" carries this incredible story forward only to the time of the banning of slavery in the British Empire. One can only hope that either Adam Hochschild or someone else writes an equally dramatic and compelling book on the saga of the worldwide struggle against slavery.

Chances do not look good. The anti-slavery movement was spearheaded by people who would today be called "the religious right" and its organization was created by conservative businessmen. Moreover, what destroyed slavery in the non-Western world was Western imperialism.

Nothing could be more jolting and discordant with the vision of today's intellectuals than the fact that it was businessmen, devout religious leaders and Western imperialists who together destroyed slavery around the world. And if it doesn't fit their vision, it is the same to them as if it never happened.

As anti-slavery ideas eventually spread throughout Western civilization, a worldwide struggle pitted the West against Africans, Arabs, Asians and virtually the entire non-Western world, which still saw nothing wrong with slavery. But Western imperialists had gunpowder weapons first and that enabled the West to stamp out slavery in other societies as well as in its own.

The review of "Bury the Chains" in the New York Times tried to suggest that the ban against the international slave trade somehow served British self-interest. But John Stuart Mill, who lived in those times, said that the British "for the last half-century have spent annual sums equal to the revenue of a small kingdom in blockading the Africa coast, for a cause in which we not only had no interest, but which was contrary to our pecuniary interest."

It was a worldwide epic struggle, full of dramatic and sometimes violent episodes, along with inspiring stories of courage and dedication. But do not expect Hollywood to make a movie about anything so contrary to their vision of the world. (Published: Feb 08, 2005)

Sunday, July 12, 2020

Environmentalism: Luxury Of The Rich

Going through the trouble of getting my smog check this weekend reminded me of one of my pet peeves in politics: wealthy environmentalists feeling moral about themselves while others (primarily the poor) pay the burden.

Here in California, in order to register your car you have to get a smog check every two years. They typically start around $50/car and go up from there, depending on the size of the car. However, if your car has the 'service engine soon' light on, for any reason, it will not pass smog. No ifs ands or buts. On top of that, if you are lucky enough to get your car serviced, thereby removing the 'service engine soon' light, you still can't smog your car...you have to drive it around for a few days, under different conditions, for atleast 20 miles before you even have a chance to pass smog.

Luckily for me, I can pay my mechanic (a family friend) to drive to San Diego and replace the part needed to remove the 'service engine soon' light. But I am reminded of how difficult and terrifying this situation was when I didn't have that luxury. When I was growing up, I had (like most of my friends and neighbors) a cheap, used, beat up, automobile, and the thought of having to pay the cost of bringing it up to smog was terrifying. Most of the time we would simply buy off the smog check operator. Giving him $50 on top of the smog fee to get him to do what was needed to 'pass' the car. California has gotten smarter about that and I hear now, it's near impossible to fake a 'pass' on smog (though I haven't needed to try). So if you have an old, beat up, car that you use to get to work and pick up your groceries with, one that is vital to your parenting, income and free time, and and it doesn't pass smog - too bad for you (don't get me started on the 'assistance' offered either), it's time to take the bus (and even here, environmentalists will cheer, as greater use of buses is encouraged). Yet, how many rich environmentalists do you think would even have to deal with a smog check problem?

The smog check is just a minor reminder of environmentalism in general: it is a luxury of the rich. The richer you are, the more you can afford to be an environmentalist. Whether we are talking about environmental land regulations, emission regulations, a gas tax, or any other contentious environmental issue, the costs are usually disproportionately paid for by the poor.

Nothing demonstrates this better than looking at the trends in global poverty and environmentalism. David Friedman writes:

Of course this means nothing to the wealthy environmentalists living in the comfort of the wealthiest countries in the world. Being outside the realm of absolute poverty gives them the luxury to be environmentalists and pontificate on the 'evils' of global warming. People in China on the other hand, are more concerned with feeding their children and reaching the standard of living that we in the west have long enjoyed.

The same general pattern applies here in the United States. The higher up on the income ladder you are, the more you can afford to be an environmentalist, and the rest of us have to hear your moral tripe and - worst of all - pay for it.

For more on this go here, here, here, here, and here. (Posted 03/04/2008)

Here in California, in order to register your car you have to get a smog check every two years. They typically start around $50/car and go up from there, depending on the size of the car. However, if your car has the 'service engine soon' light on, for any reason, it will not pass smog. No ifs ands or buts. On top of that, if you are lucky enough to get your car serviced, thereby removing the 'service engine soon' light, you still can't smog your car...you have to drive it around for a few days, under different conditions, for atleast 20 miles before you even have a chance to pass smog.

Luckily for me, I can pay my mechanic (a family friend) to drive to San Diego and replace the part needed to remove the 'service engine soon' light. But I am reminded of how difficult and terrifying this situation was when I didn't have that luxury. When I was growing up, I had (like most of my friends and neighbors) a cheap, used, beat up, automobile, and the thought of having to pay the cost of bringing it up to smog was terrifying. Most of the time we would simply buy off the smog check operator. Giving him $50 on top of the smog fee to get him to do what was needed to 'pass' the car. California has gotten smarter about that and I hear now, it's near impossible to fake a 'pass' on smog (though I haven't needed to try). So if you have an old, beat up, car that you use to get to work and pick up your groceries with, one that is vital to your parenting, income and free time, and and it doesn't pass smog - too bad for you (don't get me started on the 'assistance' offered either), it's time to take the bus (and even here, environmentalists will cheer, as greater use of buses is encouraged). Yet, how many rich environmentalists do you think would even have to deal with a smog check problem?

The smog check is just a minor reminder of environmentalism in general: it is a luxury of the rich. The richer you are, the more you can afford to be an environmentalist. Whether we are talking about environmental land regulations, emission regulations, a gas tax, or any other contentious environmental issue, the costs are usually disproportionately paid for by the poor.

Nothing demonstrates this better than looking at the trends in global poverty and environmentalism. David Friedman writes:

For someone in favor of helping poor people, the economic development of China and India is arguably the best news of the past fifty years. Development was, after all, the explicit goal of foreign economic aid, development planning, a variety of programs in the post-war period that were supposed to lift the third world out of poverty--and didn't. The fact that more than two billion people are now in the process of moving from extreme poverty towards the sort of life westerners have long lived represents an enormous improvement in the condition of the world's poor.

It also represents a sharp increase in the consumption of depletable resources and production of carbon dioxide.Take China as an example, a country where millions of people are moving out of poverty yearly. Great news for those interested in poverty. But bad news for environmentalism, as China moving from rural agricultural society to urban industrialized society means they will burn alot more coal (coal being one of the cheapest sources of energy), thereby increasing the production of carbon dioxide. Some environmentalists, seeing the contradiction try to get around it by making an argument that the environmental impact affects China (and poor areas in general) the most, but this pales in comparison to the economic impact that environmental regulations would impose. Economic development, in many inherent ways, is really at odds with environmental development.

Of course this means nothing to the wealthy environmentalists living in the comfort of the wealthiest countries in the world. Being outside the realm of absolute poverty gives them the luxury to be environmentalists and pontificate on the 'evils' of global warming. People in China on the other hand, are more concerned with feeding their children and reaching the standard of living that we in the west have long enjoyed.

The same general pattern applies here in the United States. The higher up on the income ladder you are, the more you can afford to be an environmentalist, and the rest of us have to hear your moral tripe and - worst of all - pay for it.

For more on this go here, here, here, here, and here. (Posted 03/04/2008)

Saturday, July 11, 2020

Liberals: Charitable With Your Money Only

About a year ago Arthur C. Brooks, a professor at Syracuse University, published "Who Really Cares: The Surprising Truth About Compassionate Conservatism". The conclusion: liberals are markedly less charitable than conservatives.

Some of his conclusions:

Obama is no different. Law Professor Paul Caron writes in TaxProf blog:

In contrast, John McCain has given:

For more on this see here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

Update: Ted Kennedy was no different.

Some of his conclusions:

-- Although liberal families' incomes average 6 percent higher than those of conservative families, conservative-headed households give, on average, 30 percent more to charity than the average liberal-headed household ($1,600 per year vs. $1,227).With this in mind, this news comes as no surprise:

-- Conservatives also donate more time and give more blood.

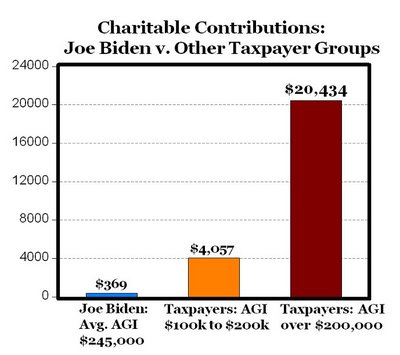

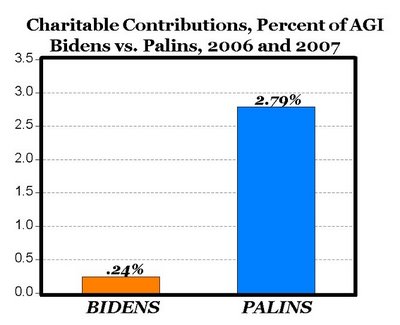

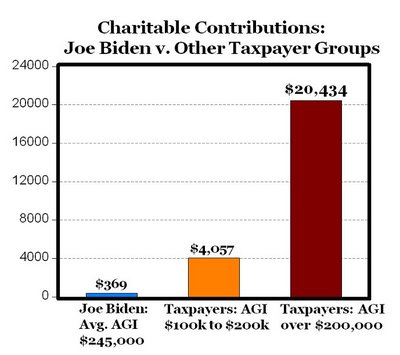

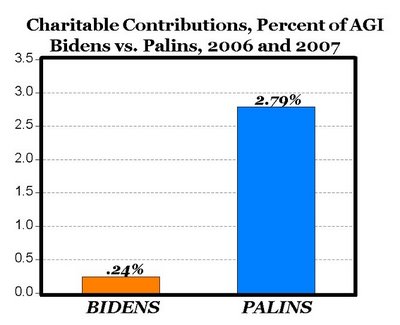

When it comes to giving money to charities, it's not even close: the Palins are almost 12 times as generous as the Bidens, when measured by charitable contributions as a percent of Adjusted Grosss Income in 2006 and 2007: 2.79% average for the Palins in those two years, vs. 0.24% for the Bidens (see top chart above).

And even though the Palins ($294,000) earned only about half the income of the Bidens ($569,000) in 2006 and 2007 combined, the Palins gave almost 6 times as much to charity ($8,205) in those two years as the Bidens ($1,375), see bottom chart above.

Obama is no different. Law Professor Paul Caron writes in TaxProf blog:

What is surprising, given the recent controversy over Obama's membership in the Trinity United Church of Christ, is how little the Obamas apparently gave to charity -- well short of the biblical 10% tithe for all seven years. In two of the years, the Obamas gave far less than 1% of their income to charity; in three of the years, they gave around 1% of their income to charity. Only in the last two years have they given substantially more as their income skyrocketed -- 4.7% in 2005 and 6.1% in 2006.The last two years being the years where he is under public scrutiny.

In contrast, John McCain has given:

Sen. John McCain, the Republican presidential candidate, has released his tax returns for the past two years, including details about the money he donated to charitable causes, The Chronicle of Philanthropy reports. In 2007, he contributed 26 percent of his total income to charity.Even the "evil" George Bush is markedly more charitable:

President and Mrs. George W. Bush certainly did their part. According to their 2005 tax return, the Bushes had taxable income of $618,694 and contributed $75,560 to charitable organizations...In other words, liberals are generous with other peoples money, certainly not their own.

For more on this see here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

Update: Ted Kennedy was no different.

Tuesday, July 7, 2020

Hunger Strikes For Raised Wages

Several students at Georgetown University staged a hunger strike to shame the University into raising the wages it pays to its janitors. Today that strike ended when the University agreed to increase janitors’ wages and fringe benefits.

I have nothing against Georgetown U. raising the amount it pays to its janitors. But the full picture of this little episode is different than the cropped snapshots that I see in the newspapers and hear on the local radio stations. The pop image is of selfless, concerned students making a noble sacrifice to help voiceless, hapless janitors get a better deal from a penny-pinching University bureaucracy.

This pop image is distorted.

Why was the pre-strike janitorial wage as low as it was? Answer: because Georgetown University discovered that, at that wage, it got as many janitors as it needed, of sufficient quality, to perform the desired cleaning services. To pay more would have been an act of charity to the janitors and not a act of commerce.

Now there’s nothing wrong with charity; I applaud it (when it’s done wisely). But why, in this case, did the hunger-striking students single out Georgetown University as an alleged malefactor? Why was the janitors’ employer targeted for its failure to extend charity?

Why didn’t the hunger-strikers demand that George Mason University or Catholic University extend charity to Georgetown University’s janitors? Or why didn’t these strikers demand that all merchants in Northwest DC extend charity to these janitors? Why didn’t the strikers give their own money as charity to the janitors? (They’re students, you say; so they don’t have much extra cash. Well, they can take out loans to give charity today to the janitors and then work after graduation to repay these loans.) Or why didn’t these hunger-striking students demand that Georgetown University increase its charitable contributions, not to its relatively well-off janitors, but to seriously poor people in sub-Saharan Africa?

I’m not being flippant. I’m quite serious. Because Georgetown University is no monopsonistic buyer of janitorial services, it must compete in the market to buy these services. The wages it pays for its janitors are, therefore, competitive. Paying anything more than these wages to secure the desired number of janitors is, therefore, charity. And while there’s nothing wrong with Georgetown University extending charity to its janitors (or to anyone else), there’s also nothing obligatory about it. The fact that Georgetown paid its janitors what it did was not, contrary to the hunger-striking student’s claims, a moral breach.

Post can be found here.

I have nothing against Georgetown U. raising the amount it pays to its janitors. But the full picture of this little episode is different than the cropped snapshots that I see in the newspapers and hear on the local radio stations. The pop image is of selfless, concerned students making a noble sacrifice to help voiceless, hapless janitors get a better deal from a penny-pinching University bureaucracy.

This pop image is distorted.

Why was the pre-strike janitorial wage as low as it was? Answer: because Georgetown University discovered that, at that wage, it got as many janitors as it needed, of sufficient quality, to perform the desired cleaning services. To pay more would have been an act of charity to the janitors and not a act of commerce.

Now there’s nothing wrong with charity; I applaud it (when it’s done wisely). But why, in this case, did the hunger-striking students single out Georgetown University as an alleged malefactor? Why was the janitors’ employer targeted for its failure to extend charity?

Why didn’t the hunger-strikers demand that George Mason University or Catholic University extend charity to Georgetown University’s janitors? Or why didn’t these strikers demand that all merchants in Northwest DC extend charity to these janitors? Why didn’t the strikers give their own money as charity to the janitors? (They’re students, you say; so they don’t have much extra cash. Well, they can take out loans to give charity today to the janitors and then work after graduation to repay these loans.) Or why didn’t these hunger-striking students demand that Georgetown University increase its charitable contributions, not to its relatively well-off janitors, but to seriously poor people in sub-Saharan Africa?

I’m not being flippant. I’m quite serious. Because Georgetown University is no monopsonistic buyer of janitorial services, it must compete in the market to buy these services. The wages it pays for its janitors are, therefore, competitive. Paying anything more than these wages to secure the desired number of janitors is, therefore, charity. And while there’s nothing wrong with Georgetown University extending charity to its janitors (or to anyone else), there’s also nothing obligatory about it. The fact that Georgetown paid its janitors what it did was not, contrary to the hunger-striking student’s claims, a moral breach.

Post can be found here.

Monday, July 6, 2020

Where Would General Motors Be Without the United Automobile Workers Union?

Where Would General Motors Be Without the United Automobile Workers Union?

04/19/2006 George Reisman

This is a question that no one seems to be asking. And so I've asked it. And here, in essence, is what I think is the answer. (The answer, of course, applies to Ford and Chrysler, as well as to General Motors. I've singled out General Motors because it's still the largest of the three and its problems are the most pronounced.)

First, the company would be without so-called Monday-morning automobiles. That is, automobiles poorly made for no other reason than because they happened to be made on a day when too few workers showed up, or too few showed up sober, to do the jobs they were paid to do. Without the UAW, General Motors would simply have fired such workers and replaced them with ones who would do the jobs they were paid to do. And so, without the UAW, GM would have produced more reliable, higher quality cars, had a better reputation for quality, and correspondingly greater sales volume to go with it. Why didn't they do this? Because with the UAW, such action by GM would merely have provoked work stoppages and strikes, with no prospect that the UAW would be displaced or that anything would be better after the strikes. Federal Law, specifically, The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, long ago made it illegal for companies simply to get rid of unions.

Second, without the UAW, GM would have been free to produce in the most-efficient, lowest cost way and to introduce improvements in efficiency as rapidly as possible. Sometimes this would have meant simply having one or two workers on the spot do a variety of simple jobs that needed doing, without having to call in half a dozen different workers each belonging to a different union job classification and having to pay that much more to get the job done. At other times, it would have meant just going ahead and introducing an advance, such as the use of robots, without protracted negotiations with the UAW resulting in the need to create phony jobs for workers to do (and to be paid for doing) that were simply not necessary.

(Unbelievably, at its assembly plant in Oklahoma City, GM is actually obliged by its UAW contract to pay 2,300 workers full salary and benefits for doing absolutely nothing. As The New York Times describes it, "Each day, workers report for duty at the plant and pass their time reading, watching television, playing dominoes or chatting. Since G.M. shut down production there last month, these workers have entered the Jobs Bank, industry's best form of job insurance. It pays idled workers a full salary and benefits even when there is no work for them to do.")

Third, without the UAW, GM would have an average unit cost per automobile close to that of non-union Toyota. Toyota makes a profit of about $2,000 per vehicle, while GM suffers a loss of about $1,200 per vehicle, a difference of $3,200 per unit. And the far greater part of that difference is the result of nothing but GM's being forced to deal with the UAW. (Over a year ago, The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that "the United Auto Workers contract costs GM $2,500 for each car sold.")

Fourth, without the UAW, the cost of employing a GM factory worker, including wages and fringes, would not be in excess of $72 per hour, which is where it is today, according to The Post-Crescent newspaper of Appleton, Wisconsin.

Fifth, as a result of UAW coercion and extortion, GM has lost billions upon billions of dollars. For 2005 alone, it reported a loss in excess of $10 billion. Its bonds are now rated as "junk," that is, below, investment grade. Without the UAW, GM would not have lost these billions.

Sixth, without the UAW, GM would not now be in process of attempting to pay a ransom to its UAW workers of up to $140,000 per man, just to get them to quit and take their hands out of its pockets. (It believes that $140,000 is less than what they will steal if they remain.)

Seventh, without the UAW, GM would not now have healthcare obligations that account for more than $1,600 of the cost of every vehicle it produces.

Eighth, without the UAW, GM would not now have pension obligations which, if entered on its balance sheet in accordance with the rule now being proposed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, will leave it with a net worth of minus $16 billion.

What the UAW has done, on the foundation of coercive, interventionist labor legislation, is bring a once-great company to its knees. It has done this by a process of forcing one obligation after another upon the company, while at the same time, through its work rules, featherbedding practices, hostility to labor-saving advances, and outlandish pay scales, doing practically everything in its power to make it impossible for the company to meet those obligations.

Ninth, without the UAW tens of thousands of workers — its own members — would not now be faced with the loss of pension and healthcare benefits that it is impossible for GM or any of the other auto companies to provide, and never was possible for them to provide. The UAW, the whole labor-union movement, and the left-"liberal" intellectual establishment, which is their father and mother, are responsible for foisting on the public and on the average working man and woman a fantasy land of imaginary Demons (big business and the rich) and of saintly Good Fairies (politicians, government officials, and union leaders). In this fantasy-land, the Good Fairies supposedly have the power to wring unlimited free benefits from the Demons.

Tenth, Without the UAW and its fantasy-land mentality, autoworkers would have been motivated to save out of wages actually paid to them, and to provide for their future by means of by and large reasonable investments of those savings — investments with some measure of diversification. Instead, like small children, lured by the prospect of free candy from a stranger, they have been led to a very bad end. They thought they would receive endless free golden eggs from a goose they were doing everything possible to maim and finally kill, and now they're about to learn that the eggs just aren't there.

It's very sad to watch an innocent human being suffer. It's dreadful to contemplate anyone's life being ruined. It's dreadful to contemplate even an imbecile's falling off a cliff or down a well. But the union members, their union leaders, the politicians who catered to them, the journalists, the writers, and the professors who provided the intellectual and cultural environment in which this calamity could take place — none of them were imbeciles. They all could have and should have known better.

What is happening is cruel justice, imposed by a reality that willfully ignorant people thought they could choose to ignore as long as it suited them: the reality that prosperity comes from the making of goods, not the making of work; that it comes from the doing of work, not from the shirking of it; that it comes from machines and methods of production that save labor, not the combating of those machines and methods; that it comes from the earning and reinvestment of profits not from seizure of those profits for the benefit of idlers, who do all they can to prevent the profits from being earned in the first place.

In sum, without the UAW, General Motors would not be faced with extinction. Instead, it would almost certainly be a vastly larger, far more prosperous company, producing more and better motor vehicles than ever before, at far lower costs of production and prices than it does today, and providing employment to hundreds of thousands more workers than it does today.

Few things are more obvious than that the role of the UAW in relation to General Motors has been that of a swarm of bloodsucking leeches, a swarm that will not stop until its prey exists no more.

It is difficult to believe that people who have been neither lobotomized nor castrated would not rise up and demand that these leeches finally be pulled off!

Perhaps the American people do not rise up because they have never seen General Motors, or any other major American business, rise up and dare to assert the philosophical principle of private property rights and individual freedom and proceed to pull the leeches off in the name of that principle.

It is easy to say, and also largely true, that General Motors and American business in general have not behaved in this way for several generations because they no longer have any principles. Indeed, they would project contempt at the very thought of acting on any kind of moral or political principle.

One of the ugliest consequences of the loss of economic freedom and respect for property rights is that it makes such spinelessness and gutlessness on the part of businessmen — such amorality — a requirement of succeeding in business. Business today is conducted in the face of all pervasive government economic intervention. There is rampant arbitrary and often unintelligible legislation. There are dozens of regulatory agencies that combine the functions of judge, jury, and prosecutor in the enforcement of more than 75,000 pages of Federal regulations alone. The tax code is arbitrary and frequently unintelligible. Judicial protection of economic freedom has not existed since 1937, when the Supreme Court abandoned it, out of fear of being enlarged by Congress with new members sufficient to give a majority to the New Deal on all issues. (Try to project the effect of a loss of judicial protection of the freedoms of press and speech on the nature of what would be published and spoken.)

Any business firm today that tried to make a principled stand on such a matter as throwing out a legally recognized labor union would have to do so in the knowledge that its action was a futile gesture that would serve only to cost it dearly. And a corporation that did this would undoubtedly also be embroiled in endless lawsuits by many of its stockholders blaming it for the losses the government imposed on it.

But none of this should stop anyone else from speaking up and making known his outrage at what the UAW has done to General Motors.

This article is copyright © 2006, by George Reisman. Permission is hereby granted to reproduce and distribute it electronically and in print, other than as part of a book and provided that mention of the author's web site www.capitalism.net is included. (Email notification is requested.) All other rights reserved. Reisman is the author of Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics (Ottawa, Illinois: Jameson Books, 1996) and is Pepperdine University Professor Emeritus of Economics. His book is available through Mises.org, Amazon.com, and on his web site. See his Mises.org Daily Articles Archive and read his interview in the Austrian Economics Newsletter. You can contact him by mail. To comment on this piece, go to the blog.

Sunday, July 5, 2020

Liberals, Race, and History: Left’s House of Cards Threatened

Liberals, Race, and History: Left’s House of Cards Threatened

By Thomas Sowell on June 1, 2005

Liberal Democrats, especially, must keep blacks fearful of racism everywhere, including in an administration whose Cabinet includes people of Chinese, Japanese, Hispanic, and Jewish ancestry, and two consecutive black Secretaries of State. Blacks must be kept believing that their only hope lies with liberals.

Not only must the present be distorted, so must the past — and any alternative view of the future must be nipped in the bud. That is why prominent minority figures who stray from the liberal plantation must be discredited, debased and, above all, kept from becoming federal judges.

A thoughtful and highly intelligent member of the California supreme court like Justice Janice Rogers Brown must be smeared as a right-wing extremist, even though she received 76 percent of the vote in California, hardly a right-wing extremist state. But desperate politicians cannot let facts stand in their way.

Least of all can they afford to let Janice Rogers Brown become a national figure on the federal bench. The things she says and does could lead other blacks to begin to think independently — and that in turn threatens the whole liberal house of cards. If a smear is what it takes to stop her, that is what liberal politicians and the liberal media will use.

It’s "not personal" as they say when they smear someone. It doesn’t matter how outstanding or upstanding Justice Brown is. She is a threat to the power that means everything to liberal politicians. The Democrats’ dependence on blacks for votes means that they must keep blacks dependent on them.

Black self-reliance would be almost as bad as blacks becoming Republicans, as far as liberal Democrats are concerned. All black progress in the past must be depicted as the result of liberal government programs and all hope of future progress must be depicted as dependent on the same liberalism.

In reality, reductions in poverty among blacks and the rise of blacks into higher level occupations were both more pronounced in the years leading up to the civil rights legislation and welfare state policies of the 1960s than in the years that followed.

Moreover, contrary to political myth, a higher percentage of Republicans than Democrats voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But facts have never stopped politicians or ideologues before and show no signs of stopping them now.

What blacks have achieved for themselves, without the help of liberals, is of no interest to liberals. Nothing illustrates this better than political reactions to academically successful black schools.

Despite widespread concerns expressed about the abysmal educational performances of most black schools, there is remarkably little interest in those relatively few black schools which have met or exceeded national standards.

Anyone who is serious about the advancement of blacks would want to know what is going on in those ghetto schools whose students have reading and math scores above the national average, when so many other ghetto schools are miles behind in both subjects. But virtually all the studies of such schools have been done by conservatives, while liberals have been strangely silent.

Achievement is not what liberalism is about. Victimhood and dependency are.

Black educational achievements are a special inconvenience for liberals because those achievements have usually been a result of methods and practices that go directly counter to prevailing theories in liberal educational circles and are anathema to the teachers’ unions that are key supporters of the Democratic Party.

Many things that would advance blacks would not advance the liberal agenda. That is why the time is long overdue for the two to come to a parting of the ways.

Friday, July 3, 2020

Talkers versus doers

Talkers versus doers

Thomas Sowell

|Posted: Jun 09, 2004 12:00 AM

Doctors and hospitals have helped but much of the improvement in our health has been due to pharmaceutical drugs that keep us from having to go to hospitals, and has been due to pharmaceutical drugs that keep us from having to go to hospitals, and have enabled doctors to head off many serious medical problems with prescriptions.

Yet the people who produce pharmaceutical drugs have been under heated political attack for years -- attacks which often do not let the facts get in their way.

During the anthrax scare of 2001, for example, the maker of the leading antidote for anthrax was accused of making "obscene profits" even though (1) the total cost of treatment with their drug was just $50 and (2) the company actually operated at a loss while they were being denounced for obscene profits.

People who know nothing about advertising, nothing about pharmaceuticals, and nothing about economics have been loudly proclaiming that the drug companies spend too much on advertising -- and demanding that the government pass laws based on their ignorance.

Today, we take the automobile so much for granted that it is hard to realize what an expansion of the life of ordinary people it represented. There was a time when most people lived and died within a 50-mile radius of where they were born.

The automobile opened a whole new world to these people. It also enabled those living in overcrowded cities to spread out into suburbs and get some elbow room. Trucks got goods to people more cheaply and ambulances got people to hospitals to save their lives.

Yet who among the people who did this are today regarded as being as big a hero as Ralph Nader, who put himself on the map with complaints about cars in general and the Corvair in particular? Hard data on automobile safety and tests conducted on the Corvair both undermined Nader's claims. But he will always be a hero to the talkers. So will those who complain about commerce and industry that have raised our standard of living to levels that our grandparents would not have dreamed of.

Home-ownership is far more widespread among ordinary people today than in the past because of entrepreneurs who have figured out how to produce more, bigger and better houses at prices that more and more people could afford. But can you name any of those entrepreneurs who have been celebrated for their contributions to their fellow human beings?

Probably not. In California, anyone in the business of producing housing is more likely to be demonized as a "developer," a word that causes hostile reactions among Californians conditioned to respond negatively -- and automatically, like Pavlov's dog.

As for computers, no one made them more usable by more people around the world than Microsoft. And no one has been hit with more or bigger lawsuits as a result.

Why can't the talkers leave the doers alone? Perhaps it is because that would leave the talkers on the sidelines, with their uselessness being painfully obvious to all, instead of being in the limelight and "making a difference" -- even if that difference is usually negative.

Thursday, July 2, 2020

The Hidden Danger of Seat Belts

The Hidden Danger of Seat Belts

By DAVID BJERKLIE Thursday, Nov. 30, 2006

How can that be? Adams' interpretation of the data rests on the notion of risk compensation, the idea that individuals tend to adjust their behavior in response to what they perceive as changes in the level of risk. Imagine, explains Adams, a driver negotiating a curve in the road. Let's make him a young male. He is going to be influenced by his perceptions of both the risks and rewards of driving a car. The considerations could include getting to work or meeting a friend for dinner on time, impressing a companion with his driving skills, bolstering his image of himself as an accomplished driver. They could also include his concern for his own safety and desire to live to a ripe old age, his feelings of responsibility for a toddler with him in a car seat, the cost of banging up his shiny new car or losing his license. Nor will these possible concerns exist in a vacuum. He will be taking into account the weather and the condition of the road, the amount of traffic and the capabilities of the car he is driving. But crucially, says Adams, this driver will also be adjusting his behavior in response to what he perceives are changes in risks. If he is wearing a seat belt and his car has front and side air bags and anti-skid brakes to boot, he may in turn drive a bit more daringly.

The point, stresses Adams, is that drivers who feel safe may actually increase the risk that they pose to other drivers, bicyclists, pedestrians and their own passengers (while an average of 80% of drivers buckle up, only 68% of their rear-seat passengers do). And risk compensation is hardly confined to the act of driving a car. Think of a trapeze artist, suggests Adams, or a rock climber, motorcyclist or college kid on a hot date. Add some safety equipment to the equation — a net, rope, helmet or a condom respectively — and the person may try maneuvers that he or she would otherwise consider foolish. In the case of seat belts, instead of a simple, straightforward reduction in deaths, the end result is actually a more complicated redistribution of risk and fatalities. For the sake of argument, offers Adams, imagine how it might affect the behavior of drivers if a sharp stake were mounted in the middle of the steering wheel? Or if the bumper were packed with explosives. Perverse, yes, but it certainly provides a vivid example of how a perception of risk could modify behavior.

In everyday life, risk is a moving target, not a set number as statistics might suggest. In addition to external factors, each individual has his or her own internal comfort level with risk-taking. Some are daring while others are cautious by nature. And still others are fatalists who may believe that a higher power devises mortality schedules that fix a predetermined time when our number is up. Consequently, any single measurement assigned to the risk of driving a car is bound to be only the roughest sort of benchmark. Adams cites as an example the statistical fact that a young man is 100 times more likely to be involved in a severe crash than is a middle-aged woman. Similarly, someone driving at 3:00 a.m. Sunday is more than 100 times more likely to die than someone driving at 10:00 a.m. Sunday. Someone with a personality disorder is 10 times more likely to die. And let's say he's also drunk. Tally up all these factors and consider them independently, says Adams, and you could arrive at a statistical prediction that a disturbed, drunken young man driving in the middle of the night is 2.7 million times more likely to be involved in a serious accident than would a sober, middle-aged woman driving to church seven hours later.

The bottom line is that risk doesn't exist in a vacuum and that there are a host of factors that come into play, including the rewards of risk, whether they are financial, physical or emotional. It is this very human context in which risk exists that is key, says Adams, who titled one of his recent blogs: "What kills you matters — not numbers." Our reactions to risk very much depend on the degree to which it is voluntary (scuba diving), unavoidable (public transit) or imposed (air quality), the degree to which we feel we are in control (driving) or at the mercy of others (plane travel), and the degree to which the source of possible danger is benign (doctor's orders), indifferent (nature) or malign (murder and terrorism). We make dozens of risk calculations daily, but you can book odds that most of them are so automatic—or visceral—that we barely notice them.

Wednesday, July 1, 2020

Slavery In Context

Do me a favor, read this and this from Michael Medved and when you are done read this blog post and tell me if their description of what Medved wrote is accurate.

After reading the two articles I responded in the comments section to correct what I saw as a false representation of what he had written. After all was said and done I simply asked them to tell me what Medved said that was in error? Which of his general points were wrong? A simple request, I thought.

Reenee, one of the co-bloggers of the blog responded with this:

I responded and then Leesee, whom I assume wrote the original post, responded with this:

This was a few days ago and so you can imagine how surprised I was to see the topic brought up again today, see here. I thought for sure this time there would be a list of errors, a real critique of what Medved wrote. Well, if you guessed not, you would have been correct. It is more of the same. More caricatures, attacks on the credentials of Medved, and references to incidental parts of his article, not a direct rebut of his main points.

Don't get me wrong. I don't agree with everything Medved wrote. There are some points he makes that are stronger than others. There is wording he uses that I would not have used. There are some points he includes that I would not have. And of course, there are some exaggerations and misleading statements...but I do buy the overall heart of his article - specifically the points I commented on the original post (slavery was universal, it was primarily the west that abolished it, and the majority of Native Americans were killed by the unintentional transfer of diseases).

The reason I was asking for a critique is because he makes many of the same arguments that a book I am reading does, Thomas Sowell's, Black Rednecks and White Liberals. Thomas Sowell backs up his claims with reputable sources, many of them respected historians. So when I saw the Medved post, and saw that he was making many of the same arguments, I thought this would be a good opportunity to see how one goes about critiquing Sowell's arguments. However, the whole exchange left me with the impression that Sowell is more right than I initially gave him credit for (how else can you explain the irrational responses and refusal to deal with his central points?).

So if you have some time, read the two Medved articles, read the follow up posts by people who found the articles inaccurate, and if you find the refutations lacking and the topic interests you more I strongly recommend you read Thomas Sowells book, Black Rednecks And White Liberals, it gives more of the historical backing and larger context of some of the general points in Medved's first article.

I want to close with a quote from a somewhat dated Thomas Sowell article:

After reading the two articles I responded in the comments section to correct what I saw as a false representation of what he had written. After all was said and done I simply asked them to tell me what Medved said that was in error? Which of his general points were wrong? A simple request, I thought.

Reenee, one of the co-bloggers of the blog responded with this:

My co-blogger's post was not misleading nor was it myopic. It was her expressing her opinion.

This country does not get off the hook for introducing slavery merely because it was being done elsewhere on the planet. Nor does it get off the hook by "abolishing it quickly" after 240 years. You might want to expand your reading to other writers other than the glossed over tomes available to most schools.

After you've finished with those books, go here, pick out the first ten history books about the indigenous people and how they were treated, and then you'll have a more well-rounded grasp on their history and what was done to them.

Everyone in this country ought to be baffled when faced with an argument that tries to mitigate or downplay or excuse the very bloody history of what our country did to people, either found here or imported, since it was founded.

That they aren't, baffles me.

And, that's all I have to say about that.In other words, still no list of errors. Simply rebuts to arguments I did not make and a recommendation of what books I should read to be more 'enlightened'.

I responded and then Leesee, whom I assume wrote the original post, responded with this:

His-Pan: That you would seek to defend Medved and ask for point by point disputation astonishes me.

Medved seeks to diminish the murder, the slavery, the genocide and the suffering, he gives a seemingly rational argument but I'm not buying it and it's my choice not to buy it. Frankly I'm a little sad you fell for his feel good take on these very sad episodes in our collective history.

Sometimes when you argue the fine points you miss the bigger picture, the fact is these things happened and putting them in so-called historical context does not diminish the crimes.

We as a gente cannot let anyone else define our reality or make less of our experience. It's your choice to buy into Medved's cleaned up history lesson and I'm just not there. Go on over to Crooks and Liars specifically Keith Olbermanns take on Medved, he called him the worst person in the world for "apologizing" for slavery, how is you don't get that?You notice a pattern here? Still no list of errors and more of the same caricatures.

This was a few days ago and so you can imagine how surprised I was to see the topic brought up again today, see here. I thought for sure this time there would be a list of errors, a real critique of what Medved wrote. Well, if you guessed not, you would have been correct. It is more of the same. More caricatures, attacks on the credentials of Medved, and references to incidental parts of his article, not a direct rebut of his main points.

Don't get me wrong. I don't agree with everything Medved wrote. There are some points he makes that are stronger than others. There is wording he uses that I would not have used. There are some points he includes that I would not have. And of course, there are some exaggerations and misleading statements...but I do buy the overall heart of his article - specifically the points I commented on the original post (slavery was universal, it was primarily the west that abolished it, and the majority of Native Americans were killed by the unintentional transfer of diseases).

The reason I was asking for a critique is because he makes many of the same arguments that a book I am reading does, Thomas Sowell's, Black Rednecks and White Liberals. Thomas Sowell backs up his claims with reputable sources, many of them respected historians. So when I saw the Medved post, and saw that he was making many of the same arguments, I thought this would be a good opportunity to see how one goes about critiquing Sowell's arguments. However, the whole exchange left me with the impression that Sowell is more right than I initially gave him credit for (how else can you explain the irrational responses and refusal to deal with his central points?).

So if you have some time, read the two Medved articles, read the follow up posts by people who found the articles inaccurate, and if you find the refutations lacking and the topic interests you more I strongly recommend you read Thomas Sowells book, Black Rednecks And White Liberals, it gives more of the historical backing and larger context of some of the general points in Medved's first article.

I want to close with a quote from a somewhat dated Thomas Sowell article:

Of all the tragic facts about the history of slavery, the most astonishing to an American today is that, although slavery was a worldwide institution for thousands of years, nowhere in the world was slavery a controversial issue prior to the 18th century.

People of every race and color were enslaved -- and enslaved others. White people were still being bought and sold as slaves in the Ottoman Empire, decades after American blacks were freed.

Everyone hated the idea of being a slave but few had any qualms about enslaving others. Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century -- and then only in Western civilization.

Among those who turned against slavery in the 18th century were George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry and other American leaders. You could research all of 18th century Africa or Asia or the Middle East without finding any comparable rejection of slavery there.

But who is singled out for scathing criticism today? American leaders of the 18th century.The full article should be read in full, see here. I'd post this response on the original blog post but then my two previous comments have already been blocked and on the last blog post there is a clear request not to. (Originally posted 10/05/2007)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)