My longest friendship was with Edgar, a friend I met in the 6th grade. He was, like me, a child of immigrant parents and he spoke primarily Spanish. He loved to joke, tell stories, and that favorite of past times, sit around with your closest friends and make fun of each other.

Unfortunately, he was also one who tended toward the criminal side of life. Since we first met, he was always getting into trouble for something, be it ditching class, smoking weed, fighting, stealing stereos, stealing cars and other things - but nothing that would make him a bad friend. He wouldn't steal from his friends, I have never in my life seen him lose his temper, he was a friend who would watch your back and who you could trust.

I remember riding my bike from Compton to his parents apartment in Gardena and later to their new spot in South Los Angeles. He introduced me to a lot of new people. Everywhere he moved, within months, he would know many people in the neighborhood. Like me, he was someone who couldn't stay in the house and met new people easily. We both would ride our bikes anywhere, on a whim. To swapmeets, malls, hang outs, anywhere our bikes would take us. Also, as crazy luck would have it, he had two cousins that were from the Mexican gang that claimed my neighborhood in Compton. Eventually, he too would join that gang and become one of its lifetime members.

Like my mom, he had a family that would give him almost free reign to do as he pleased. There were no restrictions, even at an early age, we had no curfew, no limits on where or what city we can ride our bikes to, and little supervision outside of the home. His step dad, who had spent some time in prison and I knew only casually, would sometimes pick us up if we needed it. One time, I think I was about 13 years old at the time, his step dad picked us up and instead of taking us immediately home, drove deeper into LA to a place I had never been before. He left us in the car reassuring us he would be back shortly. Hours passed, well into the night, and we were still parked. He had an old Monte Carlo with really wide back seats, so Edgar and I fell asleep in the car, waiting for him to get back. Then out of nowhere, he comes back to the car, asks Edgar to get in the back seat with me, and brings with him a, what looked like, neighborhood cluck head. A cluck head is someone who is so addicted to drugs, primarily crack cocaine and has done so much of it, that they are visually drug addicts. The people you meet in high crime neighborhoods late at night with really red eyes, dry lips, missing teeth and always begging you for change, those are cluck heads. As soon as they got into the car, he drives a few blocks more and she gets out only to return a few minutes later. Edgar and I are both still in the back seat but I don't say a word and Edgar looks like he went right back to sleep. A few minutes go by and I hear them smoking something, I hear the burning of foil paper, the sight of a lighter, and eventually realize that they are smoking crack cocaine together. After doing this for some time, he eventually leaves the area and takes us home. Years later, the same step dad would be hospitalized after jumping out of his second story window while high on PCP, he believed he could fly and nobody could convince him otherwise.

The longest friendship from Compton I had was with (lil) Sid, he lived a few houses from my house. Though he was a few years younger than me, we hung out alot. He would come to my house and we would play nintendo, baseball, and craps in the front of my house. Thinking back to those early years, I remember most his temper, whenever he would lose big he would have to go back home because he would get so frustrated with himself, sometimes in tears of anger. As the years passed Sid got older (and bigger, grew up to be one big guy) and, sadly, ended up joining the neighborhood crip gang. Though he was black, a member of a crip gang, and had a circle of friends different than mine, we continued to stay really close friends.

Sid didn't know his father and his mother was a neighborhood walker, at all hours of the day and night she would be walking all around the neighborhood, to peoples houses, to the liquor store, to the adjacent streets, all over. Sids mom was also, though not at the level of a crack head, a crack cocaine user. Though I knew before, I remember hanging out with a local drug dealer when she showed up to buy crack. She looked at me straight in the eyes and told me never to mention this to her son. I promised her that I would not, and never did - though I am sure he already knew.

My neighbors in Compton were local crips. The mom was as addicted to crack cocaine as you can get. She had missing teeth, a temper like no other, a clumsy walk, always had a cigaratte or beer in her hand and if you met her elsewhere you could easily confuse her for homeless (nonetheless, I grew up with her as a friend and neighbor, and to this day when I see her we hug and respect each other). She has three sons, the older one of which was getting into trouble since I first moved into Compton (he is now serving life in prison).

These friends and family upbringings I write about are not that rare in Compton. Almost all of my friends families I had while living in Compton have something in common with these families. Very few of them, especially my black friends, have married parents, the ones that did had a dad that beats their mom, others one that is a drug and/or alcoholic, others a dad that is currently in prison or an ex-con former gangmember (like Edgars step dad) - some have prostitute moms, some have parents that sell drugs and push them to sell drugs. I remember walking into a friends house and seeing his mom sniffing cocaine right off the living room table. It didn't bother her either, we just walked right passed her into my friends room. She was a neighborhood drug dealer and her son would later follow in her footsteps, all with his moms approval and backing. In fact, all drug dealers I knew in Compton had atleast tacit approval from their parents - several had outright encouragement.

Poverty in the United States is not primarily material, it is not primarily nutritional, it is not even primarily a lack of opportunity, though some of that still remains - poverty in the United States is primarily with the family. As the must read political scientist James Q. Wilson wrote, "There are many families with competent single moms, but they are outnumbered by the families that are harmed by the absence of a husband. From the ranks of the latter come high rates of crime and imprisonment, heavy rates of drug use, poor school performance, and a willingness to loot unguarded stores....In my opinion, the condition of the black family is the key to the persistence of a large and criminal lower class."

It is not money, or nutrition, or greater opportunity that the poor in the United States primarily need, it is a family structure that is conducive to learning, to upward mobility, and to a crime free life. When you have a large amount of friends and family - dads, brothers, uncles, and neighbors either in gangs or intimately tied to the gang culture, and a world filled with drugs, and crime, it is hard to see a way out and it is hard to learn the virtues necessary to get out. Virtues like hard work, discipline, self control, and responsibility are hard if not impossible to learn in these environments and much of government assistant is wasted or counterproductive in these situations.

As far as Edgar and Sid go, Edgar was in jail the last couple of years I lived in Compton, and the last time I saw him was when I was in my last year of college, I picked him up from jail and took him to his parents house. At this point his parents had had enough with him and refused to let him in. He promised he is a changed man and begged them to give him one last chance but they wouldn't budge. I dropped him off with some of his homies, and that is the last I saw of him. Shortly after, he would land in prison again, this time his last and he is not set to come out for a very long time. Sid, on the other hand, started to do good. After I moved out of Compton I would occasionally come back to visit and last I heard he said he was finally leaving Compton in search of a better life in Long Beach. Unfortunately, that was the last I saw of him. In another Compton visit I spotted his mom and eagerly asked her about Sid, with the impression that he is doing well in Long Beach. She informed me that he had been shot and killed in LA, and with tears already in her eyes, I asked no further questions and expressed my condolences. May he Rest In Peace. (Originally published 2/13/2007)

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Monday, June 29, 2020

Is Racism Still Important?

A continued theme on Matthew Yglesias blog is that conservatives in general are more concerned with anti-racism than racism, this is how he explains it:

Of course racism is important, very important, to those who are suffering under racism. If I was denied a job solely because of my race, I would be really pissed off and want some justice. However, as a policy issue I think racism is very low on the totem poll of problems (though not zero).

I like the way economist Walter Williams explained it:

This is much more a problem on the left than it is on the right. The left tends to see the world through the prism of "racism" (and"class warfare"), making honest dialog on race issues extremely difficult - trust me, I've tried. The right, on the other hand, has a more balanced view on these issues and because of it you are able to go further in finding a cure.

Not only does overemphasis on racism result in unintended censorship on important topics, but it also leads to a blinding force when searching for solutions. When dealing with the issues of illegitimacy rates, crime and failing public schools, for example, the progressive tries hard to find its racist connection - however strained that connection may be. This is a serious stumbling block and is one of the main reasons why real educational reforms, whether it's charter schools, vouchers, or even NCLB have all come from the right.

So I would argue that as far as real effective policy goes, emphasis on racism has now ran into significant diminishing returns, whereas the overemphasis on racism is a real roadblock to discussing important minority problems.

And it seems like Matthew Yglesias, ultimately, is not too far off. For example, in a separate post, he lists what he considers the real problems of racism today:

That is not to say that it is any less offensive to the person being statistically discriminated against but it makes a huge difference when looked at from a policy perspective. Take the claim "about an African-American man having trouble hailing a cab", as an example. The reason that Blacks have trouble hailing a cab, specifically in New York City, is because Blacks have a higher crime rate than many other groups. A cab driver, being in an especially vulnerable position, has a strong incentive to ensure his safety but at the same time he also wants to make the most money he can. So every approaching customer gets put through some sort of subconscious statistical analysis: is this person more likely to rob me? Given that the cab driver has a limited amount of information to go on, race plays an important factor. This is not unique to white cab drivers either, cab drivers of every race, including Black cab drivers, show the same tendency of picking up Black passengers less than non-Black ones. While this may be offensive, from a policy perspective there is no practical way to prevent it - as long as the cab driver has an incentive to reduce the likelihood of robbery, and as long as being Black signals a higher probability for robbery, there is always going to be the desire to resist providing a cab when the cab driver deduces the risk is too high. The same general principle applies about stereotypically “black” names, see here.

The real gains in reducing statistical discrimination come not from government fiat but from the inside, as economist Bryan Caplan states,"If you really want to improve your group's image, telling other groups to stop stereotyping won't work. The stereotype is based on the underlying distribution of fact. It is far more realistic to turn your complaining inward, and pressure the bad apples in your group to stop pulling down the average." Which is, btw, more likely when you don't see racism behind every corner.

Besides, hasn't Yglesias noticed that we have a Black President? How much of an impediment can racism really be in a country that elected its first Black president? John McWhorter has more here. (Originally published 10/30/2009)

"...most conservatives, think that the preeminent racial problem in the United States is that white people are too put upon by political correctness. Conservatives are very very very concerned about this alleged problem of anti-racism run amok. And they’re very concerned about the alleged problem of reverse discrimination. But they don’t seem concerned at all about racism or discrimination and certainly not nearly as concerned as they about helping out the poor, put-upon white man.This is actually true and though Yglesias views it as a flaw, I see it as a virtue. In fact, its one of the reasons why I find the conservative side more appealing than the progressive side. Just to be clear though, Yglesias is not saying that conservatives view racism as historically unimportant, or that racism is completely unimportant, cuz then I would agree with Yglesias that that is a flaw; no, Yglesias is chiding conservatives for not seeing todays racism as a bigger problem than todays "anti-racism".

Of course racism is important, very important, to those who are suffering under racism. If I was denied a job solely because of my race, I would be really pissed off and want some justice. However, as a policy issue I think racism is very low on the totem poll of problems (though not zero).

I like the way economist Walter Williams explained it:

Like the March of Dimes' victory against polio in the U.S., civil rights organizations can claim victory as well. At one time, black Americans did not enjoy the same constitutional guarantees as other Americans. Now we do. Because the civil rights struggle is over and won doesn't mean that all problems have vanished within the black community. A 70 percent illegitimacy rate, 65 percent of black children raised in female-headed households, high crime rates and fraudulent education are devastating problems, but they're not civil rights problems. Furthermore, their solutions do not lie in civil rights strategies.

Civil rights organizations' expenditure of resources and continued focus on racial discrimination is just as intelligent as it would be for the March of Dimes to continue to expend resources fighting polio in the U.S. Like the March of Dimes, civil rights organizations should revise their agenda and take on the big, non-civil rights problems that make socioeconomic progress impossible for a large segment of the black community.In other words, racism as a source of minority failure is not all that important anymore. Most real impediments to minority success - issues like illegitimacy rates, crime, failing public schools - are only loosely, very loosely I would argue, tied to race. But because race is such a hot button issue, these issues are difficult to talk about openly - ultimately harming the search for the cure. Bring up your concerns with crime in the ghetto, illegitimacy rates, the widening educational gap, or affirmative action and unless you walk a very tight line, you can be easily accused of racism. This censorship, namely, this "anti-racism", hampers progress on such important issues (even some progressives agree, see here).

This is much more a problem on the left than it is on the right. The left tends to see the world through the prism of "racism" (and"class warfare"), making honest dialog on race issues extremely difficult - trust me, I've tried. The right, on the other hand, has a more balanced view on these issues and because of it you are able to go further in finding a cure.

Not only does overemphasis on racism result in unintended censorship on important topics, but it also leads to a blinding force when searching for solutions. When dealing with the issues of illegitimacy rates, crime and failing public schools, for example, the progressive tries hard to find its racist connection - however strained that connection may be. This is a serious stumbling block and is one of the main reasons why real educational reforms, whether it's charter schools, vouchers, or even NCLB have all come from the right.

So I would argue that as far as real effective policy goes, emphasis on racism has now ran into significant diminishing returns, whereas the overemphasis on racism is a real roadblock to discussing important minority problems.

And it seems like Matthew Yglesias, ultimately, is not too far off. For example, in a separate post, he lists what he considers the real problems of racism today:

At any rate, I’ve made this point a million times, but it’s fascinating to me the kind of double standard conservatives apply to these issues. You never hear Rush Limbaugh decrying everyday racism against non-whites in the United States. You never hear him recounting an anecdote about an African-American man having trouble hailing a cab or being followed by a shopkeeper. He doesn’t do stories about how people with stereotypically “black” names suffer job discrimination. He doesn’t bemoan the fact that the United States has an aircraft carrier named after a fanatical segregationist.What is interesting about this list is what type of "racism" it is: specifically, statistical racism (more here and here), or what economists call statistical discrimination. This type of "racism" is very different than the invidious racism that comes to mind when we think of racism: issues like being forced to sit in the back of the bus, forced segregation, laws against interracial marriages, poll taxes and so forth. Statistical discrimination, while still offensive, is based on statistics, not bigotry.

That is not to say that it is any less offensive to the person being statistically discriminated against but it makes a huge difference when looked at from a policy perspective. Take the claim "about an African-American man having trouble hailing a cab", as an example. The reason that Blacks have trouble hailing a cab, specifically in New York City, is because Blacks have a higher crime rate than many other groups. A cab driver, being in an especially vulnerable position, has a strong incentive to ensure his safety but at the same time he also wants to make the most money he can. So every approaching customer gets put through some sort of subconscious statistical analysis: is this person more likely to rob me? Given that the cab driver has a limited amount of information to go on, race plays an important factor. This is not unique to white cab drivers either, cab drivers of every race, including Black cab drivers, show the same tendency of picking up Black passengers less than non-Black ones. While this may be offensive, from a policy perspective there is no practical way to prevent it - as long as the cab driver has an incentive to reduce the likelihood of robbery, and as long as being Black signals a higher probability for robbery, there is always going to be the desire to resist providing a cab when the cab driver deduces the risk is too high. The same general principle applies about stereotypically “black” names, see here.

The real gains in reducing statistical discrimination come not from government fiat but from the inside, as economist Bryan Caplan states,"If you really want to improve your group's image, telling other groups to stop stereotyping won't work. The stereotype is based on the underlying distribution of fact. It is far more realistic to turn your complaining inward, and pressure the bad apples in your group to stop pulling down the average." Which is, btw, more likely when you don't see racism behind every corner.

Besides, hasn't Yglesias noticed that we have a Black President? How much of an impediment can racism really be in a country that elected its first Black president? John McWhorter has more here. (Originally published 10/30/2009)

Sunday, June 28, 2020

More On Majors And Why Chicano Studies Is Garbage

A frequent topic of discussion in my family is what university, what major and the return to investment my sister should pursue after finishing high school. My dad is a man of modest means and is the only bread winner in a family of five - 3 children of which, have yet to pursue a college degree. Aside from the financial help I provide, he has nobody else to rely on. My families situation is not that different from other minorities, at some point - regardless of grants and financial aid - you have to weigh the trade-offs and cost/benefit of sending your child off to college.

Long time readers of this blog know my position, which is fundamentally that the two most important variables are: what major you choose and the grades you get. Everything else is secondary at best and more likely irrelevant. I'm so extreme in my beliefs that I advised my dad that unless my sister chooses something in the hard sciences, he refuse to pay for her education (she would still be able to get her own grants, financial aid and his blessing - just not his money). Also, despite the fact that my sister went to a good public school (my parents fake their address), took advanced classes - AP and honors Math, Physics, English, History etc - and finished near the top of her class, I still advised her to go to a Cal State. Even the relatively cheap cost of the UC's, had she applied (to avoid the temptation, she didn't even apply) and been accepted, would not have been worth the costs, IMHO. The hiring premium between say a Berkeley student and a Cal Poly student is not that much (trust me, I've done interviews for my company) and it certainly doesn't cover the long term debt difference the two schools would leave the student with (debt that comes not just from the tuition but also the living costs of living in the area). Factor in years of experience and, I strongly believe, in the long run there is no difference between the two schools that cannot be attributed to personal characteristics (IQ, work ethic, connections, etc).

This is one of the main disagreements I have with Chicano Studies and the culture it creates for minorities entering college. A year or so ago I wrote:

Well, for those who still disagree I point you to this well written advice column in The Chronicle of Higher Education. It's not completely related but it still hints at the same conclusions and remarks I mentioned before - only better written and communicated. The full article really should be read in full but for those of you short on time, I quote below his concluding remarks:

But please do read the article in full. It can be found here. (Originally published 01/07/2010)

Long time readers of this blog know my position, which is fundamentally that the two most important variables are: what major you choose and the grades you get. Everything else is secondary at best and more likely irrelevant. I'm so extreme in my beliefs that I advised my dad that unless my sister chooses something in the hard sciences, he refuse to pay for her education (she would still be able to get her own grants, financial aid and his blessing - just not his money). Also, despite the fact that my sister went to a good public school (my parents fake their address), took advanced classes - AP and honors Math, Physics, English, History etc - and finished near the top of her class, I still advised her to go to a Cal State. Even the relatively cheap cost of the UC's, had she applied (to avoid the temptation, she didn't even apply) and been accepted, would not have been worth the costs, IMHO. The hiring premium between say a Berkeley student and a Cal Poly student is not that much (trust me, I've done interviews for my company) and it certainly doesn't cover the long term debt difference the two schools would leave the student with (debt that comes not just from the tuition but also the living costs of living in the area). Factor in years of experience and, I strongly believe, in the long run there is no difference between the two schools that cannot be attributed to personal characteristics (IQ, work ethic, connections, etc).

This is one of the main disagreements I have with Chicano Studies and the culture it creates for minorities entering college. A year or so ago I wrote:

One of the many things I dislike about Chicano Studies as a major is its over emphasis on “nonprofit activism” vs “personal interest”. In the status circles of Chicano Studies students, you are admired more for your desire to ‘build a community outreach center for disadvantaged children’ than for say, getting an engineering degree and ‘making the big bucks’....a kid from the ghetto is taking an enormous risk by accepting a low salary. They are, in effect, “putting all their eggs in one basket”. And unless they are the lucky ones, they are doomed to rear their next generation of children in the very same environment they were raised in.I called it a luxury of the rich to pursue a college degree based solely on personal interest and void of personal gain. Some of my friends disagreed then. Some of my friends disagree now. They think I am too harsh in my advice on my sister. They think instead she should be able to 'pursue her dreams and interests' as if all family situations were the same (remember, my dad has finite dollars - every dollar spent on my sister is one less he can spend on the rest of the family...a high return is a necessity, not a luxury).

Well, for those who still disagree I point you to this well written advice column in The Chronicle of Higher Education. It's not completely related but it still hints at the same conclusions and remarks I mentioned before - only better written and communicated. The full article really should be read in full but for those of you short on time, I quote below his concluding remarks:

As things stand, I can only identify a few circumstances under which one might reasonably consider going to graduate school in the humanities:

Those are the only people who can safely undertake doctoral education in the humanities. Everyone else who does so is taking an enormous personal risk, the full consequences of which they cannot assess because they do not understand how the academic-labor system works and will not listen to people who try to tell them.

- You are independently wealthy, and you have no need to earn a living for yourself or provide for anyone else.

- You come from that small class of well-connected people in academe who will be able to find a place for you somewhere.

- You can rely on a partner to provide all of the income and benefits needed by your household.

- You are earning a credential for a position that you already hold — such as a high-school teacher — and your employer is paying for it.

It's hard to tell young people that universities recognize that their idealism and energy — and lack of information — are an exploitable resource. For universities, the impact of graduate programs on the lives of those students is an acceptable externality, like dumping toxins into a river. If you cannot find a tenure-track position, your university will no longer court you; it will pretend you do not exist and will act as if your unemployability is entirely your fault. It will make you feel ashamed, and you will probably just disappear, convinced it's right rather than that the game was rigged from the beginning.

But please do read the article in full. It can be found here. (Originally published 01/07/2010)

Saturday, June 27, 2020

Two Arguments In Favor Of Immigration

With the Arizona (anti-)immigration laws coming into affect soon, I have seen a lot of arguments in favor of immigration by those opposed to the Arizona laws. Most of them are either weak on economics, or miss the point completely. As a strong supporter of immigration, I thought I'd give two of my favorite arguments in favor of immigration.

My favorite argument in favor of immigration is that immigration is a huge boom to the immigrants themselves. It is, without a doubt, the strongest poverty alleviation tool in the history of man. Nothing else, no social program, no foreign aid, no economic reform, nothing, can so positively improve the lives of people like the freedom of an immigrant to move from an underdeveloped country to a developed country. The only way immigration is even debatable on humanitarian grounds is for one to assign almost zero importance to the welfare of the immigrants themselves. The argument is made stronger when you consider that immigrants also have a (small) net positive affect on the developed country. But even if you disagree, and believe that immigrants are a net loss to the receiving country, that loss would still have to be weighed against the overwhelming positive gain it gives immigrants themselves, almost always of which consist of the poorest members of the world. An impossible hurdle to overcome.

My second favorite argument in support of immigration, and this one specifically appeals to my libertarian and conservative friends, is that immigration is mutually exclusive from social programs. You have to pick: either an economy with abundant immigrants and low levels of social programs, or an economy with abundant social programs and low levels of immigrants. You can't have both. Counter intuitive you say?

Not really:

Taking the side of immigration over safety nets doesn't just make sense economically, it also makes sense on humanitarian grounds. As Bryan Caplan explained: "...unlike the welfare state, immigration has and continues to help absolutely poor people, not relatively poor Americans who are already at the 90th percentile of the world income distribution. There's no reason for libertarians to make apologies to social democrats: Libertarian defenders of immigration are the real humanitarians in the world, and the laissez-faire era of open borders without the welfare state was America's real humanitarian era." (Originally published 7/29/2010)

My favorite argument in favor of immigration is that immigration is a huge boom to the immigrants themselves. It is, without a doubt, the strongest poverty alleviation tool in the history of man. Nothing else, no social program, no foreign aid, no economic reform, nothing, can so positively improve the lives of people like the freedom of an immigrant to move from an underdeveloped country to a developed country. The only way immigration is even debatable on humanitarian grounds is for one to assign almost zero importance to the welfare of the immigrants themselves. The argument is made stronger when you consider that immigrants also have a (small) net positive affect on the developed country. But even if you disagree, and believe that immigrants are a net loss to the receiving country, that loss would still have to be weighed against the overwhelming positive gain it gives immigrants themselves, almost always of which consist of the poorest members of the world. An impossible hurdle to overcome.

My second favorite argument in support of immigration, and this one specifically appeals to my libertarian and conservative friends, is that immigration is mutually exclusive from social programs. You have to pick: either an economy with abundant immigrants and low levels of social programs, or an economy with abundant social programs and low levels of immigrants. You can't have both. Counter intuitive you say?

Not really:

Although poor immigrants are likely to support a bigger welfare state than natives do, the presence of poor immigrants makes natives turn against the welfare state. Why would this be? As a rule, people are happy to vote to "take care of their own"; that's what the welfare state is all about. So when the poor are culturally very similar to the rich, as they are in places like Denmark and Sweden, support for the welfare state tends to be uniformly strong.

As the poor become more culturally distant from the rich, however, support for the welfare state becomes weaker and less uniform. There is good evidence, for example, that support for the welfare state is weaker in the U.S. than in Europe because our poor are disproportionately black. Since white Americans don't identify with black Americans to the same degree that rich Danes identify with poor Danes, most Americans are comfortable having a relatively small welfare state.

Thus, even though black Americans are unusually supportive of the welfare state, it is entirely possible that the presence of black Americans has on net made our welfare state smaller by eroding white support for it.

Immigration is likely to have an even stronger counter-balancing effect on natives' policy preferences because, as far as most Americans are concerned, immigrants from Latin American are much more of an "out-group" than American blacks. Faced with the choice to either cut social services or give "a bunch of foreigners" equal access, natives will lean in the direction of cuts. In fact, I can't think of anything more likely to make natives turn against the welfare state than forcing them to choose between (a) helping no one, and (b) helping everyone regardless of national origin.This is not something peculiar to one blogger, this is widely recognized on the left and the right. From Paul Krugman and Matthew Yglesias on the left, to Bryan Caplan, Jeffrey Miron and David Friedman (also here) on the right.

Taking the side of immigration over safety nets doesn't just make sense economically, it also makes sense on humanitarian grounds. As Bryan Caplan explained: "...unlike the welfare state, immigration has and continues to help absolutely poor people, not relatively poor Americans who are already at the 90th percentile of the world income distribution. There's no reason for libertarians to make apologies to social democrats: Libertarian defenders of immigration are the real humanitarians in the world, and the laissez-faire era of open borders without the welfare state was America's real humanitarian era." (Originally published 7/29/2010)

Friday, June 26, 2020

The Invisible Hand vs Charity

One of the major problems I have with Chicano Studies is its overemphasis on altruistic ventures as opposed to "personal gain". Becoming a community organizer, for example, is more encouraged than becoming an engineer. This was particularly important to me last year when my sister, being in her junior year of high school, was applying to colleges. Though she had already decided on engineering as her intended major, she was having doubts and was considering a profession that "makes a difference".

I explained to her that engineering can also be used to make a difference, the two are not mutually exclusive. I also said that when you compare engineering to the highly inefficient means of "making a difference" common among chicano studies students, like community organization, one can make a very strong argument that engineering makes more of a difference - and in the process, you can make a good living doing it. She didn't seem convinced and I could tell that I needed to explain my point better. Unable to do so at the time I resorted to reminding her that there is a field in engineering that may allow her to design better prosthesis, and being that my dad lost his leg from the knee down in a work accident, she could possibly make his life and people like him better.

That satisfied her but I still thought I needed a better way to explain my point. The blog post I did later on the topic, titled "In Praise Of Personal Interest" did a better job, I wrote:

What answer do you think Peter Singer gave? Click below to see the exchange (full video, which is highly recommended, can be found here). It is a good answer, and in the end, it moves me a step closer to finally explaining my point better. Maybe I should forward this to my sister? (Originally published 05/22/2009)

I explained to her that engineering can also be used to make a difference, the two are not mutually exclusive. I also said that when you compare engineering to the highly inefficient means of "making a difference" common among chicano studies students, like community organization, one can make a very strong argument that engineering makes more of a difference - and in the process, you can make a good living doing it. She didn't seem convinced and I could tell that I needed to explain my point better. Unable to do so at the time I resorted to reminding her that there is a field in engineering that may allow her to design better prosthesis, and being that my dad lost his leg from the knee down in a work accident, she could possibly make his life and people like him better.

That satisfied her but I still thought I needed a better way to explain my point. The blog post I did later on the topic, titled "In Praise Of Personal Interest" did a better job, I wrote:

...if charity is your goal, with extra money [you would make by being an engineer] you can provide valuable resources, fund efficient charities, be a stronger role model to the next generation (three people in my family want to be engineers now, just because of my experience), provide a better future for your children, assist your family out, or, just as importantly, be a testament to those around you that hard work and dedication pay off, that there is a way out of the ghetto.

Lastly, unlike nonprofits, even if altruism is not your goal, capitalism works in such a way that when pursuing personal interest “you are led, as if by an invisible hand, to do things that improve the lives of others”.Still though, I felt like I could have explained myself better. My point does not come across as clearly as I'd like it to. Well to my surprise, while riding my bicycle to work yesterday, I was listening to a bloggingheads podcast with Philosopher Peter Singer and economist Tyler Cowen about alleviating poverty when Cowen asks Peter Singer a question that I would have asked him if I was doing the podcast, namely: what advice would you give to an 18 year old in college who has read Peter Singers book, is convinced that making a difference matters, and is considering a career as an engineer in the cell phone industry because she sees what a difference cell phones are making to the poor in Africa? Would that career choice, from an altruistic perspective, make more of a difference than, say, a person who makes 40k/year and gives 15% to the poor in India? What if the engineer never gives a dime to charity?

What answer do you think Peter Singer gave? Click below to see the exchange (full video, which is highly recommended, can be found here). It is a good answer, and in the end, it moves me a step closer to finally explaining my point better. Maybe I should forward this to my sister? (Originally published 05/22/2009)

Thursday, June 25, 2020

In Praise Of Personal Interest

One of the many things I dislike about Chicano Studies as a major is its over emphasis on "nonprofit activism" vs "personal interest". In the status circles of Chicano Studies students, you are admired more for your desire to 'build a community outreach center for disadvantaged children' than for say, getting an engineering degree and 'making the big bucks'. Obama's recent graduation speech at Wesleyan University reminded me of that. My strong dislike stems from the belief, based on three reasons, that the emphasis is counterproductive and winds up harming more than helping.

First, it is the wrong message to give to the poorest members of society who have very little to fall back on. If an upper middle class white kid decides to go into nonprofits that kid is accepting a lower standard of living than the one she grew up with but it is far different than a kid from a low income background. Even without financial assistance from the parents, the upper-middle class kid knows that if some financial disaster results, her parents can step in and help. Then there is inheritance, vacation assistance, and other perks that come with having upper middle class parents.

On the other hand, a kid from the ghetto is taking an enormous risk by accepting a low salary. They are, in effect, "putting all their eggs in one basket". And unless they are the lucky ones, they are doomed to rear their next generation of children in the very same environment they were raised in (I was shocked to hear of a Phd in Chicano Studies buying a house in Compton...you have to have a Phd in Chicano Studies to consider that progress). As I tell my family and friends who are entering the college age, "Leave the charity to the rich kids".

Second, it is inefficient. Minorities in education, in community outreach, and in most other nonprofits are literally "a dime a dozen". Another minority, because of diminishing returns, is not likely to make much of a difference. Factor in the effectivity of community outreach (very low) and the contributions that minorities in education add, and you are looking at near insignificant levels of added value.

Contrast that to the number of minorities in the for profit fields like engineering, chemistry, and technology. They are a scarcity and companies are thirsty for more. In short, you are likely to do more good for yourself and for the community as one additional engineer than as one additional member of a community outreach program.

Third, and most importantly, the two are not mutually exclusive. Making more money gives you more choices. If charity is your goal, you are likely to do more good by making alot of money than being just another 'worker bee'. When I explain this to my friends I use the analogy of Warren Buffet. I ask my friends, imagine if someone had convinced Warren Buffet to abandon what his talents are especially good at and pursue a career in nonprofits, or teaching, or politics? Now, billions later, he can do much more for charity organizations by funding the most efficient ones then by simply being another 'worker bee'.

In other words, again if charity is your goal, with extra money you can provide valuable resources, fund efficient charities, be a stronger role model to the next generation (three people in my family want to be engineers now, just because of my experience), provide a better future for your children, assist your family out, or, just as importantly, be a testament to those around you that hard work and dedication pay off, that there is a way out of the ghetto.

Lastly, unlike nonprofits, even if altruism is not your goal, capitalism works in such a way that when pursuing personal interest "you are led, as if by an invisible hand, to do things that improve the lives of others". So I say to the next generation of students, please, ignore your Chicano Studies peers, ignore Obama, and ignore anybody who tells you that making money is somehow less respectable. Your children, your family, and maybe even some charity organizations will thank you. (7/22/2008)

First, it is the wrong message to give to the poorest members of society who have very little to fall back on. If an upper middle class white kid decides to go into nonprofits that kid is accepting a lower standard of living than the one she grew up with but it is far different than a kid from a low income background. Even without financial assistance from the parents, the upper-middle class kid knows that if some financial disaster results, her parents can step in and help. Then there is inheritance, vacation assistance, and other perks that come with having upper middle class parents.

On the other hand, a kid from the ghetto is taking an enormous risk by accepting a low salary. They are, in effect, "putting all their eggs in one basket". And unless they are the lucky ones, they are doomed to rear their next generation of children in the very same environment they were raised in (I was shocked to hear of a Phd in Chicano Studies buying a house in Compton...you have to have a Phd in Chicano Studies to consider that progress). As I tell my family and friends who are entering the college age, "Leave the charity to the rich kids".

Second, it is inefficient. Minorities in education, in community outreach, and in most other nonprofits are literally "a dime a dozen". Another minority, because of diminishing returns, is not likely to make much of a difference. Factor in the effectivity of community outreach (very low) and the contributions that minorities in education add, and you are looking at near insignificant levels of added value.

Contrast that to the number of minorities in the for profit fields like engineering, chemistry, and technology. They are a scarcity and companies are thirsty for more. In short, you are likely to do more good for yourself and for the community as one additional engineer than as one additional member of a community outreach program.

Third, and most importantly, the two are not mutually exclusive. Making more money gives you more choices. If charity is your goal, you are likely to do more good by making alot of money than being just another 'worker bee'. When I explain this to my friends I use the analogy of Warren Buffet. I ask my friends, imagine if someone had convinced Warren Buffet to abandon what his talents are especially good at and pursue a career in nonprofits, or teaching, or politics? Now, billions later, he can do much more for charity organizations by funding the most efficient ones then by simply being another 'worker bee'.

In other words, again if charity is your goal, with extra money you can provide valuable resources, fund efficient charities, be a stronger role model to the next generation (three people in my family want to be engineers now, just because of my experience), provide a better future for your children, assist your family out, or, just as importantly, be a testament to those around you that hard work and dedication pay off, that there is a way out of the ghetto.

Lastly, unlike nonprofits, even if altruism is not your goal, capitalism works in such a way that when pursuing personal interest "you are led, as if by an invisible hand, to do things that improve the lives of others". So I say to the next generation of students, please, ignore your Chicano Studies peers, ignore Obama, and ignore anybody who tells you that making money is somehow less respectable. Your children, your family, and maybe even some charity organizations will thank you. (7/22/2008)

Wednesday, June 24, 2020

In Defense Of For-Profit Colleges

One of the biggest blind spots of policymakers and pundits is the inability to take target market into account. For example, you can't just compare the wages of employees at Hilton Hotels vs Motel 6's and conclude that Hilton Hotels are superior because the employees are paid more. You have to take the companies vastly different target market into account. Motel 6's target a much poorer and cost sensitive segment of the economy, and so it's understandable that they pay their employees less. In addition, Motel 6's also hire from a lower socioeconomic level than does Hilton Hotels, so again you'd expect their pay to be lower (in exchange for lower productivity, ie education, ability to speak English, etc). What seemed like a bad wrap for the poor without taking target market into account, turns out to be an overall net gain when it's included (who doubts that from the poor's perspective, Motel 6's are better than Hilton hotels?).

The same blind spot is apparent in the Wal-Mart vs union run grocery stores debate. Wal-Mart caters to a lower socioeconomic class, by hiring and providing cheaper products to those at the lower end of the income distribution. So it makes sense that their employees are paid less than their union run grocery stores counterparts, who cater to a higher socioeconomic class. Seen in that aspect, Wal-Mart is no different than the Motel 6. And since it's our ghettos and poor areas that are plagued by unemployment, empty lots and general lack of opportunities, the Wal-Mart model is a superior model for the ghettos and poor areas.

The same blind spot resurfaces when talking about for-profit colleges. When comparing for-profit colleges to non-profits, critics will primarily focus on graduation rates and default rates, taking nothing else into account. But what happens when you take target market into account?

For-profit colleges tend to cater primarily to the marginalized segments of society: working mothers, high school drop outs, older people trying to change careers, and people who are in a rush to graduate. In other words, the riskier segment of society. The very same people that the non-profit education system often ignores.

Seen from this perspective, it's expected that for-profit schools will be worse than non-profits when it comes to student debt. It's expected because they cater to riskier students, so they are going to have a larger variance of outcome - whether that is graduation rates, or student loan repayment. But catering to a riskier segment of the population is not something that should be punished, it should be encouraged. Lets remember, for-profits are actually doing what we berate businesses to do – serve those at the bottom, often forgotten by others. They are a lot better at helping students who may have messed up through high school and want to change their lives around.

And this is without even mentioning all of the other benefits that come from for-profit colleges vs traditional colleges. For example, a significantly shorter time to graduation (averaging 3 years, when non-profits are getting closer to 6 years - a huge gain in opportunity cost), more income oriented majors (even the worst of the for-profit colleges will never have such time wasted majors like Chicano Studies, for example) and a clear path towards graduation. All benefits that primarily help the marginalized segments of society.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I graduated from a for-profit institution. I got my BS in 3 years. Before that I was a high school drop out (in 10th grade) with about a 2.0 GPA. I had only a GED and no community college credits. I was also the child of a poor single mother, living in Compton, Ca. The group of friends I currently run with all have similar stories – all of us grew up poor, are minorities and graduated from the same for-profit college. None of us received any grants (my mom refused to fill out the FAFSA – she always hated anybody knowing how much she made and was convinced I would find out). More importantly, in the for-profit college I went to there were others – not a majority, but certainly a strong minority – in the same situation I grew up in. It's the privileged kids that were the exception at the for-profit college, not the the poor minorities.

All of us, also, are currently successful engineers. We all make around 6 figures a year or more. All of us with just the bachelors degree from the for-profit college (I have some undergraduate and graduate work at UCSD, but never completed a full degree there). Without a doubt, graduating from that for-profit college was the single best thing I could have done for my life. Without it, my life would have been very different. (Originally posted 11/30/2010)

The same blind spot is apparent in the Wal-Mart vs union run grocery stores debate. Wal-Mart caters to a lower socioeconomic class, by hiring and providing cheaper products to those at the lower end of the income distribution. So it makes sense that their employees are paid less than their union run grocery stores counterparts, who cater to a higher socioeconomic class. Seen in that aspect, Wal-Mart is no different than the Motel 6. And since it's our ghettos and poor areas that are plagued by unemployment, empty lots and general lack of opportunities, the Wal-Mart model is a superior model for the ghettos and poor areas.

The same blind spot resurfaces when talking about for-profit colleges. When comparing for-profit colleges to non-profits, critics will primarily focus on graduation rates and default rates, taking nothing else into account. But what happens when you take target market into account?

For-profit colleges tend to cater primarily to the marginalized segments of society: working mothers, high school drop outs, older people trying to change careers, and people who are in a rush to graduate. In other words, the riskier segment of society. The very same people that the non-profit education system often ignores.

Seen from this perspective, it's expected that for-profit schools will be worse than non-profits when it comes to student debt. It's expected because they cater to riskier students, so they are going to have a larger variance of outcome - whether that is graduation rates, or student loan repayment. But catering to a riskier segment of the population is not something that should be punished, it should be encouraged. Lets remember, for-profits are actually doing what we berate businesses to do – serve those at the bottom, often forgotten by others. They are a lot better at helping students who may have messed up through high school and want to change their lives around.

And this is without even mentioning all of the other benefits that come from for-profit colleges vs traditional colleges. For example, a significantly shorter time to graduation (averaging 3 years, when non-profits are getting closer to 6 years - a huge gain in opportunity cost), more income oriented majors (even the worst of the for-profit colleges will never have such time wasted majors like Chicano Studies, for example) and a clear path towards graduation. All benefits that primarily help the marginalized segments of society.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I graduated from a for-profit institution. I got my BS in 3 years. Before that I was a high school drop out (in 10th grade) with about a 2.0 GPA. I had only a GED and no community college credits. I was also the child of a poor single mother, living in Compton, Ca. The group of friends I currently run with all have similar stories – all of us grew up poor, are minorities and graduated from the same for-profit college. None of us received any grants (my mom refused to fill out the FAFSA – she always hated anybody knowing how much she made and was convinced I would find out). More importantly, in the for-profit college I went to there were others – not a majority, but certainly a strong minority – in the same situation I grew up in. It's the privileged kids that were the exception at the for-profit college, not the the poor minorities.

All of us, also, are currently successful engineers. We all make around 6 figures a year or more. All of us with just the bachelors degree from the for-profit college (I have some undergraduate and graduate work at UCSD, but never completed a full degree there). Without a doubt, graduating from that for-profit college was the single best thing I could have done for my life. Without it, my life would have been very different. (Originally posted 11/30/2010)

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

Should We Ban All Motels?

Mark Steckbeck, professor at Hillsdale College, writes:

The full article can be found here (broken). (Originally posted 03/14/2006)

The virtue of a free market economy is that it serves disparate tastes and talents—wants and skills. Hotels and motels, for example, differ in their locations, amenities offered, cleanliness, etc. In fact, some are utter fleabags many of us might deem unseemly. But they serve the wants of others, especially those with few or no other housing alternatives such as migrant workers and the near homeless. These customers obviously find inexpensive motels their best alternative, notwithstanding my objections.

If a minimum quality standard was legislated on motels (let’s say in the name of justice to protect the poor), forcing them to provide middle class quality and ammenities, are the customers of inexpensive motels made better off? If we force owners of motels to provide a certain level of service and quality—say a “living” quality—that forces some hotels raise their rates or to shut down, are their customers made better off? Is anyone made better off by eliminating the best market alternative currently available to them? If hoteliers refuse to treat their customers to the standards compatible with my interests I don’t want them around any way. That makes the poor better off, right?If you say no, how is this any different than someone saying this about Wal-Mart:

Look, no one should have to work in a Wal-Mart; I just plain don't care if the state loses the jobs that the chain might 'create'. What's the point of having those jobs when they don't pay a living wage and don't provide any sort of healthcare? Not to mention the way they destroy the workers' souls.Steckbeck concludes with:

Although I'm sure the author didn't intend it, his argument is a callous disregard for the poor and the unskilled. The effect is to say, "Let’s remove the only employment alternative available to many Wal-Mart workers, and for many the bottom rung needed to acquire experience and skills necessary to obtain higher paying jobs. Yeah, let’s just get rid of those."

You may not like the job or the compensation package, but like the example of inexpensive motels, remove their best alternative and they are made worse off. Be grateful that you have the skills and opportunities that allow you to earn a decent compensation package, but don't destroy someone else's best alternaitve because it isn't compatible with your idea of fairness. How noble and righteous is it to make the people who lack the skills and opportunities currently available to you worse off?

The full article can be found here (broken). (Originally posted 03/14/2006)

Monday, June 22, 2020

The Progressive Magazine On Ha-Joon Chang's Book

I got back from a five day trip to Chicago yesterday, and as such, was able to catch up on a lot of my magazine reading. A review that caught my attention was Amitabh Pal, of The Progressive Magazine, review of Ha-Joon Chang's recent book 23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism. For those unfamiliar with Ha-Joon Chang, he is a heterodox economist who is a prominent supporter of industrial policy - a view largely shunned by mainstream economists.

Amitabh Pal gives a list of the positives and negatives of the book (some I agree with, some I don't) but the part of the review that most caught my attention was this part:

I find it interesting that one of the most prominent proponents of industrial policy, in arguing for industrial policy, completely avoids dealing with a central criticism head on. But I admit, I have personally not read the book - so maybe Amitabh Pal completely missed it?

I cannot seem to find the online version of the review, but it was listed in the printed edition of April's publication. (Originally published 7/19/2011)

Amitabh Pal gives a list of the positives and negatives of the book (some I agree with, some I don't) but the part of the review that most caught my attention was this part:

Chang's Achilles heel is his fixation with industrial policy, which he views as the road to salvation for poorer nations. Only if countries protect their infant industries, nurture them in various ways, and allow them to mature can they ascend to prosperity, he says.

But a number of nations have tried this with little success, the biggest example being India, where family-run conglomerates used protectionist policies to instead foist the most shoddy, substandard products on hapless Indian consumers (the dominant car model until the late 1980s was based on a 1950s British Morris Oxford).

The obvious difference between India and Chang's native South Korea was that big business in India held sway over the state, rather than the other way around in South Korea, as delineated in Vivek Chibber's Locked In Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India. Chang sidesteps such issues.What I find most interesting is that Amitabh Pal's rebuttal is nearly identical to the standard economic criticism of industrial policy: namely, if a countries government is independent enough to properly implement industrial policy, the country likely doesn't need it, and if the government is too corrupt, industrial policy only makes things worse.

I find it interesting that one of the most prominent proponents of industrial policy, in arguing for industrial policy, completely avoids dealing with a central criticism head on. But I admit, I have personally not read the book - so maybe Amitabh Pal completely missed it?

I cannot seem to find the online version of the review, but it was listed in the printed edition of April's publication. (Originally published 7/19/2011)

Sunday, June 21, 2020

Question For Supporters Of The Minimum Wage

Given by economist Don Boudreaux:

In the U.S. in 1948, quoting my colleague Walter Williams, “the unemployment rate for white 16-17 year olds was 10.2 percent while that for blacks was 9.4 percent. Among white 18-19 year-olds, unemployment was 9.4 percent and for blacks it was 10.5 percent.” Today (October 2013) the unemployment rate for white 16-19 year olds is 19.4%; the unemployment rate for black 16-19 year olds is 36.0% - nearly double the rate of white teenage unemployment. (In 2006 – the year before the current recession began – the unemployment rate for white 16-19 year olds was 13.2%; the unemployment rate for black 16-19 years olds was 29.0% - slightly more than double the rate of white teenage unemployment.)

That is, the unemployment rate of black teenagers in 1948 was comparable to that of white teenagers, and about 2.5 times higher than the overall unemployment rate of 3.8%. Today, the unemployment rate for black teenagers is much higher than that for white teenagers, and nearly 5 times higher than the overall unemployment rate of 7.3%. (In 2006, the year before the current recession began, the unemployment rate for black teenagers was 6.3 times higher than the overall unemployment rate of 4.6%.)

How do you explain these data? Are American employers more prejudiced in 2013 than in 1948 against teenagers? More importantly, are Americans more racist in 2013 than they were in 1948?

These facts about teenage unemployment are straightforwardly explained by the standard economic theory that predicts that a legislated minimum wage causes the lowest-skilled, most poorly educated, or otherwise least-desirable workers to be the first to be fired and the last to be hired. What is your alternative explanation?

Saturday, June 20, 2020

The Scamming Beggar

I have a long standing rule to NEVER EVER give money to bums. No matter what the circumstances. I even look down on people who do. They rub me as purely emotional acts with not even one second of real thought. I do this for two reasons: one experience, the other logical. Growing up in Compton, I was approached by what we called cluck-heads daily. Crack addicts who would do anything, and I mean anything, for a $1. They would give you the most extravagant reason why that dollar was absolutely necessary. Then, after a moment of weakness, you would see them smoking that dollar - digging themselves further into the crack addiction. After years and years of this, I have developed quite a thick skin from beggars.

The logical reason has to do with the fact that it is very difficult to separate the true needy beggar from the scammer. When confronted for a donation, with such limited information, there really is no statistically significant way to know if the bum is going to use the donation for something useful, or simply another hit of drugs. Much more beneficial is to save the donation and send it to a charity devoted to helping the truly needy. They have the means of separating the sincere bum ready to change their life, from the one who just wants another hit. With such noisy information, it's much more logical to withhold your money and choose an efficient charity of your choice.

With that said, I was touched by the news article showing a New York Police officer giving a pair of winter boots to a shoeless bum. I thought, maybe in that situation that is the best thing to do, as the bum currently needs shoes, else his feet will freeze. It's an immediate, obvious need that should be fulfilled. Sending money to a charity is not going to cut it, as by then the bum could have lost his feet to frost bite. Anyway, I didn't think much more of it until later when I saw the story on CNN.

While reading the article, still torn between feelings of admiration and disapproval, I came across this interesting section:

Which cured my short lapse of judgement. (Originally published 11/30/2012)

The logical reason has to do with the fact that it is very difficult to separate the true needy beggar from the scammer. When confronted for a donation, with such limited information, there really is no statistically significant way to know if the bum is going to use the donation for something useful, or simply another hit of drugs. Much more beneficial is to save the donation and send it to a charity devoted to helping the truly needy. They have the means of separating the sincere bum ready to change their life, from the one who just wants another hit. With such noisy information, it's much more logical to withhold your money and choose an efficient charity of your choice.

With that said, I was touched by the news article showing a New York Police officer giving a pair of winter boots to a shoeless bum. I thought, maybe in that situation that is the best thing to do, as the bum currently needs shoes, else his feet will freeze. It's an immediate, obvious need that should be fulfilled. Sending money to a charity is not going to cut it, as by then the bum could have lost his feet to frost bite. Anyway, I didn't think much more of it until later when I saw the story on CNN.

While reading the article, still torn between feelings of admiration and disapproval, I came across this interesting section:

There were some who considered the officer a victim, taken in by another scam.

"This guy is only barefoot as a begging strategy," wrote David Levy. "I've been seeing him around midtown for years. I've even witnessed someone buy him slippers in a freezing day which he promptly put in his shopping cart."

"Clever stunt! The (man) is 'parked' at the entrance of a shoe shop. He got like 10 pairs that day," commented Louis Zehmke.

Which cured my short lapse of judgement. (Originally published 11/30/2012)

Friday, June 19, 2020

The Deregulation Era And Developing Countries

Lefties often label the era from the late 1970's to today as the era of deregulation where wages stagnated, income inequality increased, and overall the rich got richer at the expense of the poor. They argue that we should go back to the economic era from roughly the end of WWII, to the late 1970's. That was an era of unprecedented economic growth, rise in wages, and reduced inequality.

Now, there are various answers that could be given to such claims (see here, here, here and here for a few) but my favorite is to look at the 'deregulation era' from the eyes of poor people around the world. If your concern is the worlds truly poor - those living in absolute poverty - the 'deregulation era' is an absolute god sent.

Take Hans Rosling, who gave a Ted Talk on this very thing - showing how our preconceived notions of poor countries are extremely outdated, see here. He shows that many countries, especially in Asia, but also Latin America and Africa, that have been poor for so long are now quickly moving up the economic ladder. But this was in 2007, the leftist replies, surely it's outdated, no?

But then a couple of prominent economists noticed the same thing. MIT's Maxim Pinkovskiy and Columbia's Xavier Sala-i-Martin published a paper showing:

Matthew Yglesias quotes another study from the World Bank:

Matthew Yglesias later comments:

Notice the dramatic turnaround, starting around the 1980's and moving upwards quickly thereafter. This is all GREAT news from a developing countries perspective and it seems like the great recession hasn't slowed it down!

What would the future look like if this trend is to continue? Tim Taylor gives the numbers:

The private sector is catching on too, as Alan Taylor, a Senior Adviser at Morgan Stanley wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine:

Update: More here, here and here(pdf). (Originally published 7/29/2011)

Now, there are various answers that could be given to such claims (see here, here, here and here for a few) but my favorite is to look at the 'deregulation era' from the eyes of poor people around the world. If your concern is the worlds truly poor - those living in absolute poverty - the 'deregulation era' is an absolute god sent.

Take Hans Rosling, who gave a Ted Talk on this very thing - showing how our preconceived notions of poor countries are extremely outdated, see here. He shows that many countries, especially in Asia, but also Latin America and Africa, that have been poor for so long are now quickly moving up the economic ladder. But this was in 2007, the leftist replies, surely it's outdated, no?

But then a couple of prominent economists noticed the same thing. MIT's Maxim Pinkovskiy and Columbia's Xavier Sala-i-Martin published a paper showing:

The conventional wisdom that Africa is not reducing poverty is wrong. Using the methodology of Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin (2009), we estimate income distributions, poverty rates, and inequality and welfare indices for African countries for the period 1970-2006. We show that: (1) African poverty is falling and is falling rapidly; (2) if present trends continue, the poverty Millennium Development Goal of halving the proportion of people with incomes less than one dollar a day will be achieved on time; (3) the growth spurt that began in 1995 decreased African income inequality instead of increasing it; (4) African poverty reduction is remarkably general: it cannot be explained by a large country, or even by a single set of countries possessing some beneficial geographical or historical characteristic. All classes of countries, including those with disadvantageous geography and history, experience reductions in poverty. In particular, poverty fell for both landlocked as well as coastal countries; for mineral-rich as well as mineral-poor countries; for countries with favorable or with unfavorable agriculture; for countries regardless of colonial origin; and for countries with below- or above-median slave exports per capita during the African slave trade.The authors explain their findings here. The New Republic as well as Blue Matter blog comment here and here.

Matthew Yglesias quotes another study from the World Bank:

Just over 25% of the world’s population (1.4B people), lived in extreme poverty in 2005, according to a report released this month from the World Bank (”Global Economic Prospects 2009: Long-term prospects and poverty forecasts“). This has fallen from 42% in 1990, when the bank first published its global poverty estimates. All regions of the world have seen gains. Rapid economic growth east Asia in particular has led to a dramatic decline in global poverty. In China the share of the population getting by on $1.25 a day, or less, fell from 60% to 16%.The Economist magazine has more here.

Matthew Yglesias later comments:

Amidst all these problems in the United States, it’s worth recalling that for much of the world these are actually the best of times...

American politics is, naturally, going to remain focused primarily on the problems of Americans. But ultimately the problems of poor people in the developing world are much more severe than any of our problems, and growth in poor countries is extremely good news.Even the Huffington Post picked up on the drastic change:

In the 1990s, "people could only feed themselves, and some even starved. Children could not afford to go to school, and many could not even finish primary school," said Liu Jiandang, a 41-year-old former farmer. "Now, we've got paved roads, new houses, phones and vehicles. I run a hotel that can host 20 to 30 tourists and some rooms have TV sets, air conditioners, hot water and bathrooms."

With her profits topping 50,000 yuan ($7,000) a year, Liu can afford to send her 19-year-old son to vocational college and her 10-year-old daughter to primary school. "Our lives are so much better than before," she said.Okay - you say, but surely the financial crisis has reversed most of these trends, right? The answer is no. According to Dani Rodrik, professor at Harvard Universities International Development program, writes:

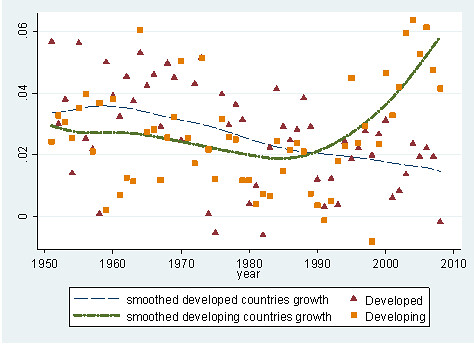

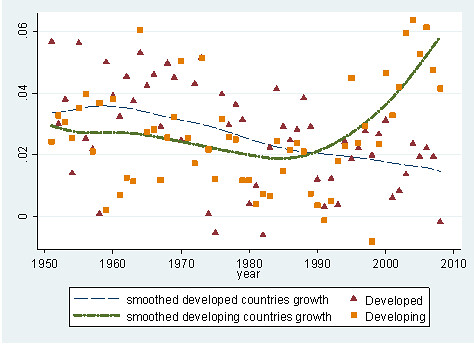

For the first time ever, developing countries as a group grew have been growing faster than industrial countries. Not only that, as the figure makes clear, the growth differential between the two groups has been widening in favor of the poor countries.

And it isn't just China, India, and a few countries that have been doing well. For a change, Africa and Latin America actually experienced some convergence with rich countries over the last decade.

Many analysts have projected these trends forward and predict rapid global growth, largely off the back of emerging and developing nations. In the words of a Citigroup report, "this time will be different."He provides this eye opening graph:

Notice the dramatic turnaround, starting around the 1980's and moving upwards quickly thereafter. This is all GREAT news from a developing countries perspective and it seems like the great recession hasn't slowed it down!

What would the future look like if this trend is to continue? Tim Taylor gives the numbers:

To get a sense of the change, compare the rank order of the economies of the world in 2009 and 2050. In 2009, the U.S. is the world's largest economy. By 2050, U.S. economy will be about 2.5 times as large--and is projected to be in third place in absolute size, behind China and India. What other countries move up the rankings notably by 2050? Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, Nigeria, and Vietnam. To my 20th century mindset, some of those countries just don't seem like global economic heavyweights. Time to start adjusting my mind to the coming realities.More can be found on his blog post here.

The private sector is catching on too, as Alan Taylor, a Senior Adviser at Morgan Stanley wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine:

A broad range of economic figures suggest that emerging markets are catching up to developed markets. As the Great Recession fades, this trend is likely to continue. The emerging-market history of low growth and high volatility is fading, while developed markets are experiencing more instability and financial impairments. Emerging markets have decreased their debt-to-GDP ratios, even as developed markets, including the United States and some in Europe, are letting theirs rise. In a sign of convergence between emerging and developed markets, health and schooling levels in emerging-market countries are now comparable to those seen in developed markets around 1975, with the gap continuing to narrow. And average levels of political and economic freedom in emerging markets have also improved dramatically in the last two decades. Although emerging markets have not yet achieved parity with developed markets…they now appear more stable and better positioned to enjoy sustained growth than they did a generation ago.Even Jay Ulfelder is convinced, he writes:

To my mind, the trends Alan Taylor identifies are the start of the big development story of the 21st century. After a century in which the global political economy was primarily characterized by the yawning gap in wealth and power between the so-called First and Third Worlds, that gap is finally narrowing. Economic growth is accelerating in countries long mired in a “poverty trap,” and the economic and political benefits of that trend are extending to more and more of the world’s human population. Hundreds of millions of people still live in abject poverty, under authoritarian rule, or both, but the share of the global population living in deep poverty is notably lower than it was just a couple of decades ago, and the economic takeoffs occurring in many long-poor countries suggest that trend is only broadening.I leave you with a quote from a study on this very thing from the Brookings Institute (pdf) :

The greatest surprise, however, is the one taking place in Sub-Saharan Africa. Between 1980 and 2005, the region’s poverty rate had consistently hovered above 50 percent. Given the continent’s high population growth, its number of poor rose steadily. The current period is different. For the first time, Sub-Saharan Africa’s poverty rate has fallen below 50 percent. The total number of poor people in the region is falling too.If you consider all humans of equal value, regardless of race or nationality, the 'deregulation era' has to be considered a great era and a positive change over previous periods of human history - and this is true, even assuming the worst case assumptions of the liberals and lefties of the world.

Update: More here, here and here(pdf). (Originally published 7/29/2011)

Friday, June 12, 2020

Beverly Hills As The USA

Imagine that you lived in Beverly Hills, among the richest people in the United States. Some of your friends were the kids of executives at Fortune 500 companies. Others were the kids of famous Doctors, Lawyers, and some were the kids of hedge fund managers. While all relatively rich, assume there was quite a range of wealth from really rich, to filthy rich.

Further assume, that one day, a bleeding heart liberal starts feeling bad for the really rich. Her complaints are along the lines of: "The really rich can't eat out at the $500/plate restaurants, they have to settle for the $100/plate restaurants, or, god forbid, make sandwiches at home". Her complaints continue: "The really rich can't afford the Lamborghini's or Ferrari's, they have to get by with the - GASP! - BMW's and Mercedes Benz's". Worst yet, "the really rich actually have to live in mansions with no ocean view, or golf courses". Most heartbreaking of all, "the really rich have to actually prioritize their lifestyle and set a budget. They can't go to Europe on a moments notice, they can't eat out everyday".